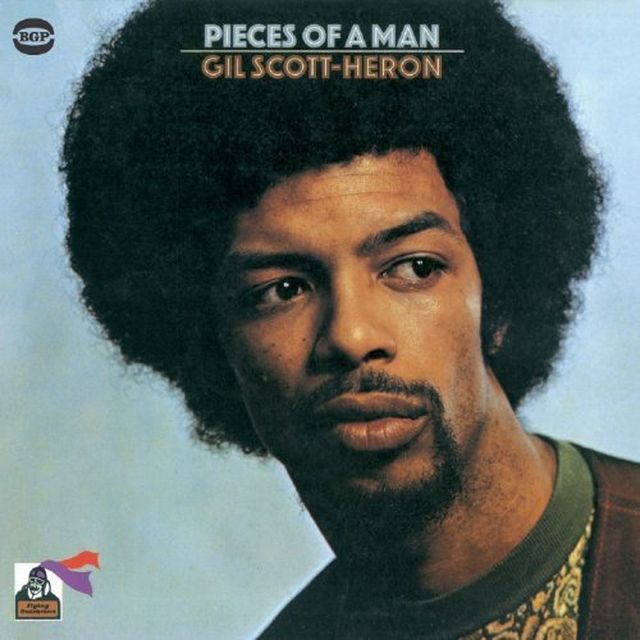

Gil Scott-Heron ¦ Pieces Of A Man

CHF 41.00 inkl. MwSt

LP (Album, Gatefold)

Nicht vorrätig

Release

Veröffentlichung Pieces Of A Man:

1971

Hörbeispiel(e) Pieces Of A Man:

Pieces Of A Man auf Wikipedia (oder andere Quellen):

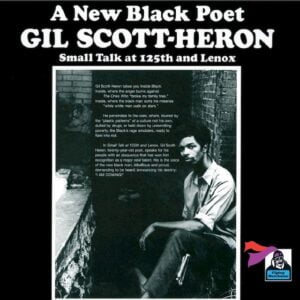

Pieces of a Man is the debut studio album by American poet Gil Scott-Heron. It was recorded in April 1971 at RCA Studios in New York City and released later that year by Flying Dutchman Records. The album followed Scott-Heron's debut live album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox (1970) and departed from that album's spoken word performance, instead featuring compositions in a more conventional popular song structure.

Pieces of a Man marked the first of several collaborations by Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson, who played piano throughout the record. It is one of Scott-Heron's most critically acclaimed albums and one of the Flying Dutchman label's best-selling LP's. Earning modest success after its release, Pieces of a Man has received retrospective praise from critics. Music critics have suggested that Heron's combination of R&B, soul, jazz-funk, and proto-rap influenced the development of electronic dance music and hip hop. The album was reissued on compact disc by RCA in 1993.

Background and recording

Before pursuing a recording career, Scott-Heron focused on a writing career.[2] He published a volume of poetry and his first novel, The Vulture, in 1970.[3] Subsequently, Scott-Heron was encouraged by jazz producer Bob Thiele to record and released a live album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox (1970).[2] It was inspired by a volume of poetry of the same name and was well received by music critics.[4]

Pieces of a Man was recorded at RCA Studios in New York City on April 19 and 20 in 1971.[5] The album's first four tracks were written by Scott-Heron, and the last seven tracks were co-written by Scott-Heron and keyboardist Brian Jackson, who backs Scott-Heron with Pretty Purdie & the Playboys.[5] The album was produced by Thiele,[5] who was known for working with jazz artists such as Louis Armstrong and John Coltrane.[2]

Music and lyrics

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The album's music is rooted in the blues and jazz influences, which Scott-Heron referred to as "bluesology, the science of how things feel."[3] The album features Gil Scott-Heron exercising his singing abilities in contrast to his previous work with poetry. It also contains more conventional song structures than the loose, spoken-word feel of Small Talk.[6]

On the album's jazz elements, music critic Vince Aletti wrote, "the songs have a loose, unanchored quality that sets them apart from both R&B and rock work. Scott-Heron sings straight-out, with an ache in his voice that conveys pain, bitterness and tenderness with equal grace and, in most cases, subtlety. Frequently the nature of the jazz backing is so free that the vocals take on an independent, almost a cappella feeling which Scott-Heron carries off surprisingly well."[6] Uncut writes that "Heron adopts his trademark jazz-funk sound, underpinned by the great Ron Carter on bass, with Hubert Laws' flute fluttering about like an elusive bird of paradise".[7] Sputnikmusic's Nick Butler notes its latter eight songs as "in line with the soul of the very early '70s - think a Curtis that replaces an orchestra with a chamber band, or a What's Going On that replaces head-in-the-clouds wistfulness with earthy indignation, or a There's A Riot Goin' On without the drugs".[8]

Problems playing these files? See media help.

"Lady Day and John Coltrane" was written by Scott-Heron as an homage to influential jazz musicians Billie Holiday and John Coltrane. His lyrics discuss the ability of music to rid people of the personal problems of alienation and existentialism in the modern world. The album features two of Scott-Heron's most well-known songs, "Home Is Where the Hatred Is", which was later a hit for R&B singer Esther Phillips, and "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", which was originally featured on his debut album Small Talk in spoken word form. "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" is a melodic, somber composition of the narrator's dangerous and hopeless environment, presumably of the ghetto, and how its effects take a toll on him. Scott-Heron's lyrics demonstrate these themes of social disillusionment and hopelessness in the first verse and the chorus.[citation needed]

Unlike other songs on the album, "Save the Children" and "I Think I’ll Call It Morning" are optimistic dedications to joy, happiness, and freedom. The title track, described by journalist and music writer Vince Alleti as the album's best song, is a lyrically cinematic account of a man's breakdown after losing his job as witnessed by his son.[6] Scott-Heron's lyricism on the album has been acclaimed by critics, as the lyrics for "Pieces of a Man" received praise for its empathetic narration.[6] The album's opening track, "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised", is a proto-rap track with lyricism criticizing the United States government and mass media. Considered a classic in the rap genre, the song features many political references, unadorned arrangements, pounding bass lines and stripped-down drumbeats.[9] The song's structure and musical formula would later influence the blueprint of modern hip hop. Because of the song's spoken word style and critical overtones, it has often been referred to as the birth of rap.[10]

Release and reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Billboard | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Guardian | |

| Melody Maker | |

| Pitchfork | 9.0/10[15] |

| Sputnikmusic | 3.5/5[8] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | B+ ( |

| Uncut | |

Pieces of a Man was released in 1971 by Flying Dutchman Records and fared better commercially than Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. Sales began to increase two years after its release, following Scott-Heron's and Jackson's departure from Flying Dutchman to Strata-East before they recorded Winter in America (1974). Pieces of a Man entered the Top Jazz Albums chart on June 2, 1973.[17] The album peaked at number 25 on the chart and remained on the chart for six weeks until July 7, 1973.[17] "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" was released as a radio single with "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" as the b-side. However, it did not chart.[9] Pieces of a Man was reissued in the United States in 1993 on compact disc by RCA

Upon its release, Pieces of a Man received little critical attention except for praise by Rolling Stone. Later, the album gained much critical acclaim, as it was praised for Scott-Heron's lyrics, political awareness, and its influence on hip hop.[9] Despite little mainstream success or critical notice during its release, music journalist Vince Aletti of Rolling Stone praised the album in a July 1972 article, stating, "Here is an album that needs discovering. It's strong, deeply soulful and possessed of that rare and wonderful quality in this time of hollow, obligatory "relevance" – intelligence.... the material is tough and real, "relevant" while avoiding, on the one hand, empty cliche and, on the other, fierce rhetoric, its own kind of cliche.... It may not be easy to find, but it's an involving, important album (especially so because of its successful and accessible use of jazz) and it's worth looking for."[6] The following year, Roger St. Pierre of NME hailed the album as "the sound of the black revolution".[18]

Pieces of a Man received stronger retrospective reviews from music critics. Adam Sweeting of The Guardian praised the album in an August 2004 article, calling it a "pioneering mix of politics, protest and proto-rap poetry, set to a musical jazz-funk hybrid."[13] BBC Online described Pieces of a Man as a "great example of his lyrical prowess and perfectly showcases the depths of his vocal talent."[19]

Legacy and influence

The album has earned a larger legacy thanks to the influential proto-rap song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised". In a 1998 interview with the Houston Press, Scott-Heron discussed how much of the album was overshadowed by the controversial song and the social-consciousness displayed:

[It] was the only political piece [on the album].... Very few people heard 'Save the Children', 'Lady Day and John Coltrane' or 'I Think I Call It Morning'. They just missed the point. The point became one of the 11 pieces. The least inventive one on the album was the one that was the most heralded.... Maybe people were intimidated by the things that we felt were normal to comment on because they were part of our lives.... To ignore part of your life and not speak on it because it might intimidate somebody is not to be very mature.[10]

In a review of the album, Nick Dedina of Rhapsody noted the album's influence on modern music forms, stating "Dance and hip-hop have borrowed (or stolen) so much from this album that it's easy to forget how original Scott-Heron's mix of soul, jazz, and pre-rap once was."[20] In 1996, radio station WXPN ranked Pieces of a Man number 100 on its list of The 100 Most Progressive Albums,[citation needed] and in 2005 it was included in Blow Up's list of The 600 Essential Albums.[citation needed] The blend of sound and instrumentation featured on Pieces of a Man later inspired many neo-soul artists in the 1990s.[21]

Heron's works have greatly impacted and influenced hip-hop and in 2018, rapper Mick Jenkins titled his sophomore studio album after this album as an homage to Heron.[22]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson except where noted

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" | Scott-Heron | 3:10 |

| 2. | "Save the Children" | Scott-Heron | 4:28 |

| 3. | "Lady Day and John Coltrane" | Scott-Heron | 3:37 |

| 4. | "Home Is Where the Hatred Is" | Scott-Heron | 3:23 |

| 5. | "When You Are Who You Are" | 3:24 | |

| 6. | "I Think I'll Call It Morning" | 3:31 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Pieces of a Man" | 4:55 |

| 2. | "A Sign of the Ages" | 4:04 |

| 3. | "Or Down You Fall" | 3:14 |

| 4. | "The Needle's Eye" | 4:51 |

| 5. | "The Prisoner" | 9:26 |

Personnel

Musicians

- Gil Scott-Heron – guitar, piano, vocals

- Hubert Laws – flute, saxophone

- Brian Jackson – piano

- Burt Jones – electric guitar

- Ron Carter – bass

- Bernard Purdie – drums

- Johnny Pate – conductor

Production

- Bob Thiele – production

- Bob Simpson – mixing

- Charles Stewart – cover photo

Charts

| Chart | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[23] | 168 |

| US Top Jazz Albums (Billboard)[17] | 25 |

References

- ^ Backus, Rob (1976). Fire Music: A Political History of Jazz (2nd ed.). Vanguard Books. ISBN 091770200X.

- ^ a b c Bush, John. "Gil Scott-Heron". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Biography. Retrieved 2012-04-26.

- ^ a b Bordowitz, Hank. "Gil Scott-Heron". American Visions: June 1, 1998.

- ^ Columnist. "Review: Small Talk at 125th and Lenox". Billboard: 14: October 2, 1971

- ^ a b c Track listing and credits as per liner notes for Pieces of a Man CD reissue

- ^ a b c d e Aletti, Vince (July 1972). "Pieces of a Man". Rolling Stone.

- ^ a b Staff (1998). Various Artists - Righteous Brother - Review - Uncut.co.uk. Uncut. Retrieved on 2011-06-12.

- ^ a b Butler, Nick (November 13, 2009). Gil Scott-Heron - Pieces of a Man (staff review) | Sputnikmusic. Sputnikmusic. Retrieved on 2011-06-12.

- ^ a b c d Azpiri, Jon. "Pieces of a Man". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Catching Up with Gil - Music - Houston Press". Village Voice Media. Archived from the original on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Columnist. "Review: Pieces of Man". Billboard: 60. December 11, 1971.

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2002). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise 4th ed.). Virgin Books. p. 1099.

- ^ a b Adam Sweeting. Review: Pieces of a Man. The Guardian. Retrieved on 2009-07-31.

- ^ Johnstone, Nick. "Review: Pieces of a Man". Melody Maker: 169. November 1999.

- ^ Burney, Lawrence (December 13, 2020). "Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man". Pitchfork. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Hull, Tom (June 28, 2021). "Music Week". Tom Hull – on the Web. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Billboard Music Charts - Search Results - Pieces of a Man Gil Scott-Heron". Nielsen Business Media. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces Of A Man (Philips 6369 415)". Rock's Backpages. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ O'Donnell, David. Review: Pieces of a Man. BBC Online. Retrieved on 2009-07-31.

- ^ Dedina, Nick. Review: Pieces of a Man Rhapsody. Retrieved on 2009-07-31.

- ^ "Brian Jackson at All About Jazz". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ Ivey, Justin (October 25, 2018). "Mick Jenkins drops 'Pieces of a Man' LP". HipHopDX.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Gil Scott-Heron – Pieces of a Man" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

Bibliography

- Nick Johnstone (1999). Melody Maker History of 20th Century Popular Music. Bloomsbury, London, UK. ISBN 0-7475-4190-6.

- Gary Graff; Josh Freedom du Lac; Jim McFarlin (1998). Musichound R&B: The Essential Album Guide. foreword by Huey Lewis, Kurtis Blow. Omnibus Press, London, UK. ISBN 0-8256-7255-4.

- Pieces of a Man album liner notes by Gil Scott-Heron and Alex Dutilh. Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

External links

- Pieces of a Man at Discogs

- Sound Check: Pieces of a Man — By Vibe

- Album Review at Must Hear

| Studio albums |

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live albums |

| ||||||

| Compilations |

| ||||||

| Singles |

| ||||||

| Other songs | |||||||

| Related topics | |||||||

Artist(s)

Veröffentlichungen von Gil Scott-Heron die im OTRS erhältlich sind/waren:

I’m New Here ¦ We’re New Again: A Reimagining By Makaya McCraven ¦ Pieces Of A Man ¦ Free Will ¦ Small Talk At 125th And Lenox

Gil Scott-Heron auf Wikipedia (oder andere Quellen):

Gil Scott-Heron (* 1. April 1949 in Chicago, Illinois; † 27. Mai 2011 in New York[3]) war ein US-amerikanischer Musiker und Dichter.

In Scott-Herons Musik vereinen sich Elemente aus Funk, Jazz, Soul und lateinamerikanischer Musik. Er arbeitete in seinen Stücken häufig mit Sprechgesang (Spoken Word) und gilt daher als einer der wichtigsten Wegbereiter der Hip-Hop- und Rap-Musik. Seine Texte sind meist von politischen oder sozialen Inhalten geprägt.

Zu seinen bekanntesten Stücken gehören The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, We Almost Lost Detroit, The Bottle, Johannesburg, Angel Dust und Lady Day and John Coltrane.[4]

Leben

Kindheit und Jugend

Schon früh brachte ihm sein Vater Gil Heron (1922–2008)[5] das Klavierspielen und Lesen bei. Dieser war der erste schwarze Fußballspieler bei Celtic Glasgow. Seine Eltern trennten sich bald, und Scott-Heron wuchs bei seiner Großmutter im Bundesstaat Tennessee auf. Hier lernte er die ländliche afroamerikanische Kultur und Lebensweise der Südstaaten kennen, aber auch einen starken Rassismus. So war er eins von drei nicht-weißen Kindern, die zum Zwecke der Integration in eine weiße Grundschule in Jackson geschickt wurden.

Da er diesen Druck nicht mehr ertrug, zog er zu seiner Mutter, einer Bibliothekarin, die mittlerweile in der Bronx (New York) lebte. Dort ging er zur High School, wo er Arbeiten des Harlem-Renaissance-Poeten Langston Hughes und des von den Beatpoeten, aber auch der afroamerikanischen Bürgerrechtsbewegung beeinflussten LeRoi Jones (später Amiri Baraka) kennenlernte. Diese sollten seine Art zu schreiben sowohl inhaltlich als auch stilistisch stark prägen. Später zog er mit seiner Mutter in eine lateinamerikanisch geprägte Nachbarschaft im New Yorker Viertel Chelsea.

Scott-Heron wurde an der Lincoln University in Oxford, Pennsylvania angenommen. Hier lernte er Brian Jackson kennen, mit dem er später lange Jahre zusammenarbeitete. Er war aber nach eigenen Aussagen die ganze Zeit mit den Arbeiten an seinem ersten Roman, The Vulture (Der Aasgeier), beschäftigt und verließ die University nach einem guten Jahr wieder. Kurzfristig besuchte er auch die Johns-Hopkins-Universität in Baltimore. 1970 veröffentlichte er seinen Debütroman, der viel Anerkennung fand.

Beginn der musikalischen Karriere

Durch die guten Besprechungen seines Debütromans lernte Scott-Heron den Jazz-Produzenten Bob Thiele kennen, der schon mit Legenden wie Louis Armstrong und John Coltrane gearbeitet hatte. Dieser ermöglichte ihm im Jahre 1970, sein erstes Album Small Talk at 125th & Lenox Ave. aufzunehmen, auf dem er sozialkritische Texte aus seinem gleichnamigen Gedichtband rezitierte. Er kombinierte sie mit Conga-Rhythmen und anderen percussiven Elementen.

Im Jahre 1971 veröffentlichte er den Nachfolger Pieces of a Man. Zum ersten Mal war Scott-Heron mit einer vollen Band im Studio, Thiele konnte für den Soundtrack zu Scott-Herons Texten einige renommierte Jazz-Musiker wie Ron Carter (Bass), Eddie Knowles und Charlie Saunders (Percussion) versammeln. Das Album enthielt eines von Scott-Herons bis heute bekanntesten Stücken, das medien- und kapitalismuskritische Lied The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.

Im darauf folgenden Jahr veröffentlichte er seinen zweiten Roman, The Nigger Factory, und sein drittes Album Free Will. Dieses sollte sein letztes für das Label Flying Dutchman sein, mit dem er sich zerstritt. Das folgende Album, Winter in America, nahm er für Strata East auf. Dieses veröffentlichte er gemeinsam mit seinem langjährigen musikalischen Partner, dem Pianisten und Songwriter Brian Jackson, der bereits auf den vorigen Alben gewirkt hatte. Das Album enthielt den Titel The Bottle, das in den Clubs New Yorks und später auch im Radio zum Hit wurde und eines seiner beliebtesten Stücke wurde. Scott-Heron und Jackson formten in den folgenden Jahren eine enge musikalische Partnerschaft, Jackson leitete praktisch Scott-Herons Midnight-Band.

Kommerzieller Erfolg

1975 wurde er von Clive Davis als der erste Künstler für das neue Label Arista Records verpflichtet, wo er für zehn Jahre blieb. Hier wurde mehr darauf geachtet, Songs in die Charts zu bringen, was mit der Singles Johannesburg (1975; Platz 29 der R&B-Charts) mäßig gelang. 1978 nahm sich der Produzent Malcolm Cecil Scott-Herons Musik an. Dieser hatte in den frühen 1970ern, der Hochphase des Funk, unter anderem mit den Isley Brothers und Stevie Wonder gearbeitet.

1980 trennte sich Scott-Heron von Brian Jackson, im selben Jahr veröffentlichten sie ihr letztes gemeinsames Album mit dem Titel 1980. In den folgenden Jahren arbeitete Scott-Heron mit Produzenten wie Nile Rodgers und Bill Laswell zusammen. 1985 wurde er nach der Veröffentlichung eines Best Of-Albums von seiner Plattenfirma Arista entlassen.

Rückzug und Kultstarstatus

Er zog sich aus dem Musikgeschäft zurück, tourte aber weiter um die Welt, wo er im Rahmen der Retromusikwelle, aber auch von Rap- und Hip-Hop-Fans wieder gefeiert wurde. 1993 unterschrieb er wieder einen Vertrag mit der Firma TVT-Records und veröffentlichte das hochgelobte Album Spirits (1994), das unter anderem den Track Message to the Messengers enthielt, in dem er die jungen Rapper dazu aufrief, Verantwortung für ihre Kunst und die Community zu übernehmen.

1994 trat er in einem „Spoken-Word“-Special von MTV auf.

Sein letztes Buch, der Gedichtband Now & Then (2001), erschien in seinem eigenen Verlag, Brouhaha Books. 2001 kam er wegen des Besitzes von einem Gramm Kokain für ein Jahr ins Gefängnis. Nachdem er im Oktober 2002 entlassen worden war, arbeitete er unter anderem wieder mit dem Kollegen Brian Jackson. 2003 filmte Don Letts im Auftrag der BBC eine Dokumentation über Scott-Herons Leben. Im selben Jahr kam Scott-Heron erneut wegen Besitzes illegaler Drogen ins Gefängnis, aus dem er ein Jahr später wieder entlassen wurde. Im Dezember 2005 wurde er in New York erneut wegen Drogenbesitzes verhaftet. Scott-Herons langjährige Kokainabhängigkeit ist Gegenstand zahlreicher Kontroversen.

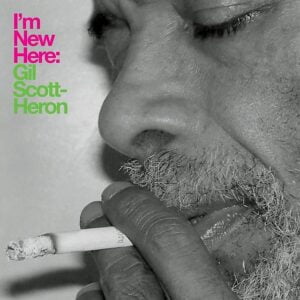

Am 8. Februar 2010 erschien mit I’m New Here sein erstes Album seit 1994.[6] Im Februar 2011 veröffentlichte der Londoner Produzent Jamie xx eine Remixversion des Albums unter dem Titel We’re New Here.

Gil Scott-Heron starb im Mai 2011 im Alter von 62 Jahren an den Folgen von Aids.[7]

Politik

Scott-Heron beschäftigte sich in seinen Songs vor allem mit den sozialen Realitäten der Afroamerikaner und der gesellschaftlichen Situation in den USA. Er sympathisierte mit der Bürgerrechtsbewegung der 1960er Jahre. Ab 1975 wandte er sich in seinen Texten den Problemen der „Dritten Welt“ zu, so beispielsweise Südafrikas. Anfang der 1980er wandte er sich scharf gegen die Politik Ronald Reagans, explizit in Songs wie B-Movie und Re-Ron. Von Anfang an textete er auch über die Probleme der Gesellschaft mit Drogen.

Diskografie

Studioalben

- 1970: Small Talk at 125th & Lenox Ave (1970; Flying Dutchman Records)

- 1971: Pieces of a Man (Flying Dutchman Records)

- 1972: Free Will (Flying Dutchman Records)

- 1974: Winter in America (Strata-East Records)

- 1975: The First Minute of a New Day – The Midnight Band (Arista Records)

- 1976: From South Africa to South Carolina (Arista Records)

- 1976: It’s Your World (Arista Records) (teilweise live)

- 1977: Bridges (Arista Records)

- 1978: Secrets (Arista Records)

- 1980: 1980 (Arista Records)

- 1980: Real Eyes (Arista Records)

- 1981: Reflections (Arista Records)

- 1982: Moving Target (Arista Records)

- 1994: Spirits (TVT Records)

- 2010: I’m New Here (XL Recordings)[8]

- 2020: We’re New Again – A Reimagining by Makaya McCraven[9]

Gastauftritte / Features

- 1996: Ron Holloway – Scorcher (Titel: Is That Jazz?, Blue Collar)

- 2000: Talib Kweli & Hi-Tek – Train Of Thought (Titel: The Blast)

- 2009: Malik & the OG’s – Rhythms of the Diaspora (Titel: Black and Blue)

Livealben

- 1990: Tales of Gil Scott-Heron and His Amnesia Express (Arista Records)

- 1994: Minister of Information (Peak Top Records)

- 2004: Save the Children – Live in Concert (Delta Music)

- 2023: Legend In His Own Mind (feat. Amnesia Express) - Live Bremen 1983

Kompilationen

- 1974: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised (Flying Dutchman Records)

- 1979: The Mind of Gil Scott-Heron (Arista Records)

- 1984: The Best of Gil Scott-Heron (Arista Records)

- 1990: Glory – The Gil Scott-Heron Collection (Arista Records)

- 1998: The Gil Scott-Heron Collection Sampler: 1974–1975 (TVT Records)

- 1998: Ghetto Style (Camden Records, UK:

Silber)

Silber) - 1999: Evolution and Flashback: The Very Best of Gil Scott-Heron (RCA)

- 2005: Gil Scott-Heron & Brian Jackson - Messages

Buchveröffentlichungen

- 1970: Small Talk at 125th and Lenox: a Collection of Black Poems. World Publishing Co., New York.

- 1970: The Vulture. World Publishing Co., New York, ISBN 0-86241-528-4.

- 1972: The Nigger Factory. Dial Press, New York, ISBN 0-86241-527-6.

- 1990: So Far, So Good. Third World Press, Chicago, ISBN 0-88378-133-6.

- 2001: Now and Then: The Poems of Gil Scott-Heron. Canongate Publishing Ltd., Edinburgh, ISBN 0-86241-900-X.

- 2012: The Last Holiday: A Memoir (postum: Autobiographie), Canongate Books, Edinburgh 2012, ISBN 978-0-85786-301-0. (Rezension in: The Guardian, 5. Febr. 2012)

Filme mit und über Gil Scott-Heron

- 1982: Black Wax. Live-Video und -DVD mit einem Konzertmitschnitt von Robert Mugge, aufgenommen 1982 in Washington D.C.

- 1991: Gil Scott-Heron and his Amnesia Express - Tales of Gil. Konzertmitschnitt und Interview mit Kevin Le Gendre

- 1988: Freedom Beat. The Video Image Entertainment

- 1979: No Nukes. Produktion: CBS, Fox Video

- 1989: Jazz Shorts. Produktion: Rhapsody Films Inc.

- 2003: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. Fernseh-Dokumentation, Großbritannien, Regie: Don Letts, Produktion: BBC, Filmseite der BBC.

- 2007: Gil Scott-Heron & Amnesia Express - The Paris Concert. Recorded live at the New Morning - Paris - July 23rd 2001, DVD, 120 Min.

Quellen

- ↑ Chartquellen: DE CH UK US

- ↑ Auszeichnungen für Musikverkäufe: UK

- ↑ „Gil Scott-Heron, Voice of Black Protest Culture, Dies at 62“, AP / New York Times, 28. Mai 2011

- ↑ siehe John Coltrane

- ↑ Roddy Forsyth: „Celtic’s first black player, Gil Heron, dies“, Daily Telegraph, 30. November 2008, Nachruf

- ↑ Soulpoet Gil Scott-Heron – Guck mal, wer da grollt!, Spiegel Online, 7. Februar 2010

- ↑ Gil Scott-Heron in der Notable Names Database (englisch)

- ↑ Die Rückkehr des Spoken Word-Hero Gil Scott-Heron (Memento vom 14. Februar 2010 im Internet Archive)

- ↑ Besprechung (Musikexpress)

Weblinks

- Werke von und über Gil Scott-Heron im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

- Gil Scott-Heron bei IMDb

- Offizielle Seite von Scott-Heron

- Christian Broecking: „Ihr nehmt die Kids zu ernst“, die tageszeitung, 18. November 2005

- Zum Tode Gil Scott-Herons: Bob Dylans schwarzer Bruder, Spiegel Online, 28. Mai 2011

- Zum Tod von Gil Scott-Heron, Faz.net, 28. Mai 2011

- I am the original Die Rückkehr des Poeten Gil Scott-Heron (Sende-Manuskript) (PDF; 157 kB)

| Personendaten | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Scott-Heron, Gil |

| KURZBESCHREIBUNG | US-amerikanischer Musiker und Dichter |

| GEBURTSDATUM | 1. April 1949 |

| GEBURTSORT | Chicago, Illinois, USA |

| STERBEDATUM | 27. Mai 2011 |

| STERBEORT | New York, USA |

Same artist(s), but different album(s)...

-

Gil Scott-Heron ¦ Small Talk At 125th And Lenox

CHF 22.00 inkl. MwSt In den Warenkorb -

Gil Scott-Heron ¦ Free Will

CHF 22.00 inkl. MwSt In den Warenkorb -

Gil Scott-Heron ¦ I’m New Here

CHF 28.00 inkl. MwSt In den Warenkorb -

Gil Scott-Heron & Makaya McCraven ¦ We’re New Again: A Reimagining By Makaya McCraven

CHF 36.00 inkl. MwSt In den Warenkorb -

Gil Scott-Heron & Makaya McCraven ¦ We’re New Again: A Reimagining By Makaya McCraven

CHF 29.00 inkl. MwSt In den Warenkorb