Nina Simone ¦ Little Girl Blue

CHF 33.00 inkl. MwSt

LP (Kompilation)

Nicht vorrätig

Zusätzliche Information

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Inhalt | |

| Ausgabe |

Release

Veröffentlichung Little Girl Blue:

1959

Hörbeispiel(e) Little Girl Blue:

Little Girl Blue auf Wikipedia (oder andere Quellen):

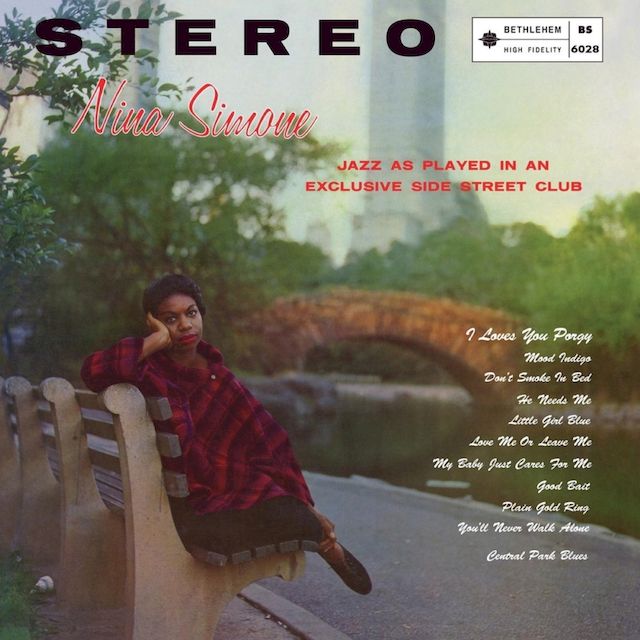

Little Girl Blue: Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club is the debut studio album by Nina Simone. Recorded in late 1957, it was eventually released by Bethlehem Records in February 1959.[1][2][3] Due to the length of time the album had taken to be released and the lack of any promotional single either immediately before or alongside the album, Simone would become disillusioned with Bethlehem and sign with Colpix Records in April 1959. She recorded the tracks for her second album - what would become The Amazing Nina Simone - the same month.[4] However, in May Bethlehem finally released a single, "I Loves You, Porgy" and gave Simone her first hit later that year, peaking at number 18 on the pop charts, and number 2 on the R&B charts. Helped by the profile of the single, the album too went on to become a chart success.[5]

In 1987, the track "My Baby Just Cares for Me" became a massive UK and European hit. The album was reissued, now with the title of single, and with a new cover and the tracks in a different order. This release eventually became subject to a legal dispute.[6][7] Later releases of the album include bonus tracks from the same recording session.[8][9]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

Overview

Recording

In spring 1957, while playing gigs in Philadelphia, Simone recorded a demo (which is believed to be the basis of the unofficial Simone album Gifted & Black released in 1970).[12] A few months later, as Alan Light tells it in What Happened, Miss Simone? - A Biography (2011), someone at Bethlehem Records in New York heard the demo recordings and became "interested in signing her to the label".[5] Nadine Cohodas, in Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone (2010), writes: Bethlehem "employed Lee Kraft as an occasional talent scout. He brought musical prospects to Gus Wildi, Bethlehem’s founder, and then Wildi and his associates decided if they wanted to make a record. Kraft had heard Nina at a club in Philadelphia and thought Bethlehem should record her." However, continues Cohodas, there is another version to the story. "Vivian Bailey, a Philadelphia businessman who first heard Nina at the Rittenhouse, said he had arranged for her to make a demo [...] He took the tape to New York and played it for Wildi. 'Her beautiful and unique vocal quality caused us to sign her immediately to a recording contract,' Wildi recalled."[13]

In December 1957, writes Light, Simone "went to New York and recorded thirteen songs backed by bassist Jimmy Bond and drummer Tootie Heath [...] The selections were essentially the songs she played as her set at the time but, given the time restraints of a studio recording, without her extended improvisations."[5] Mauro Boscarol (of the Nina Simone Timeline) writes that the album was recorded in late 1957, possibly December, but the precise date is not known; and that the session lasted 13 hours and 14 songs were recorded.[4] Cohodas agrees with the problem about designating the correct date, and corroborates 14 as the number of tracks recorded.[14] Given that the session was the only one Simone ever recorded for Bethlehem, the songs eventually released show that there were, as Boscarol and Cohodas claim, 14 tracks recorded at the session.[15]

At the time of the recording session, Simone was in her mid-20s and still aspiring to be a classical concert pianist, so she immediately sold the rights for the album to Bethlehem for $3,000 (equal to US$31,682 in 2023). According to Simone's later account, she didn't really enjoy the session, no more than her gigs at the time, as she 'still considered herself on a musical detour dictated by financial necessity'; upon returning to Philadelphia, she "immersed herself in Beethoven for three days straight".[16] The Bethlehem deal would eventually cost her royalty profits of more than a million dollars.[17]

Release

Simone was also dissatisfied by the time it took for Bethlehem to release the album and the lack of effort the record company took in promoting her.[5] However, unbeknownst to Simone, Bethlehem was in financial trouble. "Wildi found himself in a cash crunch, and in the middle of 1958 he sold a half interest in Bethlehem to Syd Nathan, who ran King Records out of Cincinnati"; furthermore there were to be "professional differences between Wildi and Nathan".[16] All these factors led to disruption at Bethlehem, and affected the release of Simone's album significantly.

The album was first announced around a year after it had been recorded in Billboard magazine in December 1958.[4] But nothing happened. Then in the 10 January 1959 issue of Cash Box, another premier American music industry trade magazine of the time, the 'Record Ramblings' column posted news out of Philadelphia: "Now that the Xmas rush is over the entire wax business in town is looking forward, with great expectancy, towards ’59 [...] King’s Al Farrio back from the vacation scene while Mario D’Aullaria goes on his after the hectic Christmas weeks. The boys both very high on the new [...] femme-jazz newcomer Nina Simone."[18] The album was then announced in the following issue dated 17 January 1959 in 'January Album Releases' with the eponymous title Nina Simone.[19] However, it seems, once again, nothing happened for a few more weeks.

The album finally appears to have been released in early February 1959. In the 14 February edition of Cash Box there was another passing mention in 'Record Ramblings' as well as a listing in 'February Album Releases', this time with the title Little Girl Blue, although with a typo calling Simone by the name 'Nina Simons'.[20][21] The album featured 11 of the tracks from the late 1957 recording session.

Title

The title of the album also appears to have caused some confusion. The first copies of the album were released with Nina Simone's name on the front of record sleeve, and the title reading: Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club. In March, for instance, the Philadelphia Tribune ran an advertisement for a gig Simone was playing in Atlantic City at the Club Harlem, which told readers with some hyperbole that in addition to being the "Nation’s newest sensation," she also had an album out: Jazz as Played in an Exclusive East Side Street Club.[22] This had "apparently been one of the proposed titles for Little Girl Blue and was featured as a subtitle in some versions."[22] Furthermore, while Cash Box had listed the album's title as Little Girl Blue in its 14 February edition 'February Album Releases', when the album entered the charts later in the year, it would list it as simply Nina Simone. For instance, the 22 August edition of Cash Box still lists the album as Nina Simone (while at position number 32 on its Top 100 Best Selling Tunes), the title Little Girl Blue being used for the 29 August edition onward (as it reached position number 27).[23][24] Later releases of the album would sometimes use one title or the other, such as Little Girl Blue (1992 Extended Version) and Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club (2002 Extended Version and Remaster).[8][25]

Promotion

Adding to Simone's disillusionment with Bethlehem, the company had also not issued a lead single to promote the album, either immediately before or immediately after the album release. As Alan Light tells it "part of Simone's frustration with Bethlehem came from their resistance to issuing a single". However, "Sid Mark, a disc jockey at WHAT in Philadelphia [...] had started playing her recording of "I Loves You, Porgy" on air, sometimes multiple times in a row."[5] When Bethlehem became aware of this, they apparently rushed to issue it as a single. "I Loves You, Porgy" was released in May 1959, the 30 May edition of Cash Box writing in their 'Record Reviews' section that it was "a beautifully sensitive performance".[26] Within a few months it had become a hit, peaking at number 18 on the pop charts, and number 2 on the R&B charts. Helped by the success of the single, the album too went on to become a hit.[5]

Aftermath

However, in the meantime, Simone had already began talking to Colpix Records about a new contract, going on to sign with them in April 1959. So soon after Little Girl Blue was out, and before Bethlehem had released "I Loves You, Porgy", Simone recorded her second album: The Amazing Nina Simone. Colpix released the lead single "Chilly Winds Don't Blow" in June 1959, just a week or so after Bethlehem rush released "I Loves You, Porgy".[27] Ironically, "I Loves You, Porgy" was a hit single, and "Chilly Winds Don't Blow" didn't chart.Ref. missing

The success of "I Loves You, Porgy" resulted in Bethlehem going on to exploit their Simone recordings for the next couple of years, all without her consent. On the one hand, the following March they released the album Nina Simone and Her Friends (1960). This compilation album had four tracks each from Simone, Carmen McRae, and Chris Connor (all three artists had left the label by this time). With respect to the Simone tracks, the album featured, along with "I Loves You, Porgy", the remaining three cuts from the 1957 recording session. On the other hand, Bethlehem would go on to release a series of singles. Thus over the next couple of years Simone singles would come both from the new material she was recording for Colpix, and from the 1957 Bethlehem session. Bethlehem would go on to release every track from that session either as A-side or B-side (and sometimes both) with the final single appearing in August 1962.

Track listing

Fourteen tracks were recorded at the December 1957 session for the album, of which eleven of the songs were included in the release of Little Girl Blue in February 1959.[28]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mood Indigo" | Duke Ellington, Barney Bigard, Irving Mills | 4:04 |

| 2. | "Don't Smoke in Bed" | Willard Robison | 3:14 |

| 3. | "He Needs Me" | Arthur Hamilton | 2:31 |

| 4. | "Little Girl Blue" | Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart | 4:19 |

| 5. | "Love Me or Leave Me" | Walter Donaldson, Gus Kahn | 3:24 |

| 6. | "My Baby Just Cares for Me" | Walter Donaldson, Gus Kahn | 3:38 |

| 7. | "Good Bait (instrumental)" | Count Basie, Tadd Dameron | 5:28 |

| 8. | "Plain Gold Ring" | George Stone (aka Earl Burroughs) | 3:57 |

| 9. | "You'll Never Walk Alone (instrumental)" | Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II | 3:49 |

| 10. | "I Loves You, Porgy" | DuBose Heyward, George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin | 4:12 |

| 11. | "Central Park Blues (instrumental)" | Nina Simone | 6:52 |

Remaining tracks from the 1957 recording session

These tracks would appear on the contemporary album Nina Simone and Her Friends (1960) and as singles (either A-sides or B-sides) over the period of 1959-1962. The British Parlaphone label as part of their 'Bethlehem Series' issued in 1962 a single called "The Intimate Nina Simone", with "I Loves You, Porgy" added to the three tracks.[29] Some later editions of the album would include them as bonus tracks, such as Little Girl Blue (1992 Extended Version) and Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club (2002 Remaster).

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands" | Traditional | 3:12 |

| 2. | "For All We Know" | J. Fred Coots, Sam M. Lewis | 4:03 |

| 3. | "African Mailman (instrumental)" | Nina Simone | 3:08 |

Personnel

Contemporary singles from the album

Initially, Bethlehem Records released no singles from Little Girl Blue, either before nor immediately after the album came out in February 1959. However, after Simone signed to Colpix Records in April of that year, Bethlehem rushed out the 7" "I Loves You, Porgy" and scored a hit. Bethlehem would then go on to release a series of singles from the Little Girl Blue album and the non-album tracks from the 1957 recording session over the next couple of years. During this series of single releases, every track of the album and session was released on single as either (and sometimes both) A-sides or B-sides.[30][31]

| Year | Month | Title: A Side / B Side | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | May | "I Loves You, Porgy" / "Love Me or Leave Me" | Both tracks from Little Girl Blue |

| 1959 | September | "He Needs Me" / "Little Girl Blue" | Both tracks from Little Girl Blue |

| 1959 | November | "Don't Smoke in Bed" / "African Mailman" | A: Little Girl Blue / B: Non-album track; subsequently appeared on the Nina Simone and Her Friends (1960) compilation album |

| 1960 | January | "Mood Indigo" / "Central Park Blues" | Both tracks from Little Girl Blue |

| 1960 | February | "For All We Know" / "Good Bait" | A: Non-album track; previously appeared on the Nina Simone and Her Friends (1960) compilation album / B: Little Girl Blue |

| 1960 | May | "You'll Never Walk Alone" / "Plain Gold Ring" | Both tracks from Little Girl Blue |

| 1960 | July | "Central Park Blues" / "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands" | A: Little Girl Blue - already appeared on single as a B-side / B: Non-album track; previously appeared on the Nina Simone and Her Friends (1960) compilation album |

| 1962 | August | "My Baby Just Cares for Me" / "He Needs Me" | A: Little Girl Blue / B: Little Girl Blue - already appeared on single as a B-side |

"My Baby Just Cares for Me" would be released as a single (both in its original form and as a 12" remix) in 1987, and become a hit in the UK then Europe.[32][33] The extended remix would go on to be included in the 2002 remaster of Little Girl Blue, renamed Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club.

Significant reissues

My Baby Just Cares for Me (1987)

This album was a simple re-issue of Little Girl Blue but with a new title, cover, and the tracks in a different order. This re-issue was occasioned by the success of the single 'My Baby Just Cares For Me' in 1987, and the album led with this track. "My Baby Just Cares for Me" - which closed the original edition of Little Girl Blue - became a top 10 hit in the United Kingdom after it was used in a 1987 perfume commercial.[34] This single then went on to hit the top 10 in several European single charts and peaked at number one in the Dutch Top 40.[33] The album was released in the wake of this. In 1989, Cohodas reports, Simone hired Steven Ames Brown, a San Francisco lawyer who specialized in royalty recovery. Together they "sued a California distributor, Street Level Trading, and the British-based Charly Records for breach of contract in a licensing deal made in 1987 for Nina’s Bethlehem recordings. The lawsuit charged that the two defendants were in breach of the deal and had committed fraud in the way they executed the arrangement. Nina claimed she was owed $200,000." In a slight reversal, Nina "had been so outspoken in criticizing Charly for failing to pay her proper royalties that the label filed a defamation suit against her in a London court and added Brown to the litigation, too, after he spoke out on her behalf. All the legal maneuvering tied up any royalty payments until Nina’s suit was settled for an undisclosed sum in the summer of 1990. As part of the settlement Charly dropped the defamation claims."[7]

Little Girl Blue (1992 Extended Version)

Little Girl Blue was reissued by Bethlehem in 1992 on CD (Bethlehem 30042), with the three additional tracks from the 1957 session which had previously appeared during the 1959-1962 period as 7" vinyl single tracks (either A-sides or B-sides) and on the vinyl compilation album Nina Simone and Her Friends.[8]

Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club (2002 Remaster)

In 2002 the album was remastered and reissued under the subtitle of the original title, Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club, by Charly / Snapper Music (SNAP 216 CD). As well as including the three session tracks like the 1992 re-issue, this album also included - anachronistically - "My Baby Just Cares for Me (Extended Version)".[35] When the reissued single had been a hit in 1987, there was also a twelve inch single mix created, named the "Special Extended Smoochtime Version", with a 5.23 running time. This is the version of the track that is labelled "My Baby Just Cares for Me (Extended Version)" and closes Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club.

References

- ^ "February Album Releases" (PDF). Cash Box. New York: The Cash Box Publishing Co. Inc. 14 February 1959. p. 29. Retrieved 18 December 2022 – via World Radio History.

- ^ Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David. "The Bethlehem Records Story". Both Sides Now Publications. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2009). Goldmine Record Album Price Guide (6th ed.). London: Penguin. p. 2123. ISBN 9781440229169.

- ^ a b c Boscarol, Mauro (2011). "Timeline". The Nina Simone Database. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Light, Alan (2016). What Happened, Miss Simone? - A Biography. New York: Crown Archetype. p. Chapter 4.

- ^ Taleveski, Nick (2006). Rock Obituaries - Knocking On Heaven's Door. Omnibus Press. p. 594. ISBN 9781846090912.

- ^ a b Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 341–2.

- ^ a b c "Bethlehem Album Discography, Part 3".

- ^ "Nina Simone: Jazz As Played In An Exclusive Side Street Club", Charly. Accessed 9 June 2016.

- ^ AllMusic review

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ Acker, Kerry (2004). Nina Simone. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 52.

- ^ Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 76–7.

- ^ Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 77.

- ^ BCP-6028/SBCP-6028 in the Bethlehem Discography by David Edwards and Mike Callahan (2014).

- ^ a b Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 78.

- ^ Simone. I Put a Spell on You. p. 60.

- ^ "Record Ramblings - Here and There - Philadelphia" (PDF). Cash Box. World Radio History. 10 January 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "January Album Releases" (PDF). Cash Box. World Radio History. 17 January 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ "Record Ramblings - Here and There - Philadelphia" (PDF). Cash Box. 26: World Radio History. 14 February 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "February Album Releases" (PDF). Cash Box. 29: World Radio History. 14 February 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Cohodas, Nadine (2010). Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 82–3.

- ^ "Cash Box TOP 100 Best Selling Tunes on Records" (PDF). Cash Box. 5: World Radio History. 22 August 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Cash Box TOP 100 Best Selling Tunes on Records" (PDF). Cash Box. 4: World Radio History. 29 August 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Nina Simone: Jazz As Played In An Exclusive Side Street Club", Charly. Accessed 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. 34: World Radio History. 30 May 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Record Ramblings" (PDF). Cash Box. 48: World Radio History. 13 June 1959. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Bethlehem Discography", BCP-6028/SBCP-6028

- ^ "The Intimate Nina Simone" at Discogs

- ^ "Nina Simone". Discogs. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Nina Simone". 45cat. 1 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Taleveski, Nick (2006). Rock Obituaries - Knocking On Heaven's Door. Omnibus Press. p. 594. ISBN 9781846090912.

- ^ a b "De Nederlandse Top 40 - week 52, 1987" (in Dutch). Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Taleveski, Nick (2006). Rock Obituaries - Knocking On Heaven's Door. Omnibus Press. p. 594. ISBN 9781846090912.

- ^ "Nina Simone: Jazz As Played In An Exclusive Side Street Club", Charly. Accessed 9 June 2016.

External links

Artist(s)

Veröffentlichungen von Nina Simone die im OTRS erhältlich sind/waren:

Sunday Morning Classics ¦ I Put A Spell On You ¦ The Montreux Years ¦ Little Girl Blue ¦ Nina Simone And Her Friends ¦ Greatest Hits

Nina Simone auf Wikipedia (oder andere Quellen):

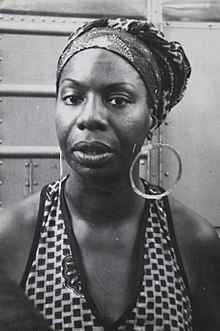

Nina Simone (bürgerlich Eunice Kathleen Waymon; * 21. Februar 1933 in Tryon, North Carolina, USA; † 21. April 2003 in Carry-le-Rouet, Frankreich) war eine US-amerikanische Jazz- und Bluessängerin, Pianistin, Songschreiberin und Bürgerrechtsaktivistin.

Leben

1933–1954: Frühes Leben

Nina Simone war das sechste von acht Kindern. Ihre Mutter war eine Methodistenpredigerin, und ihr Vater arbeitete als Entertainer und Frisör und in einer chemischen Reinigung.[1] Bereits im Alter von drei oder vier Jahren begann sie mit dem Klavierspielen. Das erste Lied, das sie lernte, war God Be With You, Till We Meet Again. Sie zeigte Talent am Klavier und trat in ihrer örtlichen Kirche auf.

Ihr Konzertdebüt gab sie mit klassischer Musik im Alter von 12 Jahren. Später erzählte Simone, dass ihre Eltern, die in der ersten Reihe Platz genommen hatten, gezwungen waren, in den hinteren Teil des Saals zu gehen, um Platz für die Weißen zu machen.[2] Sie sagte, dass sie sich weigerte zu spielen, bis ihre Eltern wieder nach vorne gebracht wurden,[3] und dass dieser Vorfall zu ihrem späteren Engagement in der Bürgerrechtsbewegung beitrug.[4] Simones Musiklehrer half bei der Einrichtung eines Sonderfonds, um ihre Ausbildung zu finanzieren,[3] anschließend wurde ein lokaler Fonds eingerichtet, um ihre weitere Ausbildung zu unterstützen. Mit Hilfe dieses Stipendiums konnte sie die Allen High School for Girls in Asheville, North Carolina, besuchen.

Nach einem Studium an der renommierten Juilliard School in New York City wollte sie ihre Ausbildung in Philadelphia am Curtis Institute of Music abschließen, wurde jedoch nicht zugelassen. Simone vertrat die Auffassung, dass sie aus rassistischen Gründen nicht zugelassen wurde.[5] Mitarbeiter vom Curtis Institute bestritten dies, Curtis habe schon lange schwarze Studentinnen und Studenten zugelassen.[6] Im Jahr, als sich Simone bewarb, wurden im Fach Klavier von 72 Bewerberinnen und Bewerbern nur drei angenommen.[7] Im Jahr 2003, wenige Tage vor ihrem Tod, verlieh ihr das Institut ein Ehrendiplom.[8]

Über einen Job als Klavierlehrerin kam Nina Simone zum Gesang und improvisierte von Anfang an eigene Stücke. Sie wählte den Nachnamen Simone, weil sie ein Fan der Schauspielerin Simone Signoret war. Ihr Gesangs- und Klavierstil war von Nellie Lutcher beeinflusst, deren Karriere ungefähr zu der Zeit endete, als Nina Simone bekannt wurde.[5] Nina Simone vermied den Ausdruck Jazz und nannte ihre Musik Black Classical Music.

1954–1964: Frühe Erfolge

1957 veröffentlichte sie in New York ihr erstes Album auf Bethlehem Records, ein Konzert 1959 in der New York City Town Hall machte sie in den USA und in Europa bekannt. Von ihren Fans wurde sie ehrfürchtig als „Hohepriesterin des Soul“ bezeichnet. In den 1960er-Jahren engagierte sie sich in der US-amerikanischen Bürgerrechtsbewegung. Mit Liedern wie Mississippi Goddam und To Be Young, Gifted, and Black (Liedtext von Weldon Irvine) wurde sie eine der musikalischen Leitfiguren dieser Bewegung.

1961 heiratete sie den New Yorker Polizisten Andrew „Andy“ Stroud (1925–2012), der später ihr Manager wurde und einige Songs für sie schrieb. 1962 brachte sie die gemeinsame Tochter Lisa Celeste Stroud zur Welt, die unter dem Künstlernamen Lisa Simone als Sängerin bekannt wurde. 1971 wurde die Ehe geschieden.

1964–1974: Bürgerrechtszeit

1964 wechselte Simone den Plattenvertrieb von der amerikanischen Firma Colpix zur niederländischen Philips Records, was eine Änderung des Inhalts ihrer Aufnahmen bedeutete. Sie hatte schon immer Lieder in ihr Repertoire aufgenommen, die sich auf ihr afroamerikanisches Erbe bezogen, wie z. B. Brown Baby von Oscar Brown und Zungo von Michael Olatunji auf ihrem Album Nina at the Village Gate von 1962. Auf ihrem Debütalbum für Philips, Nina Simone in Concert (1964), thematisierte sie in dem Song Mississippi Goddam erstmals die Rassenungleichheit in den Vereinigten Staaten.[9] Damit reagierte sie auf die Ermordung von Medgar Evers am 12. Juni 1963 und den Bombenanschlag auf die 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, am 15. September 1963, bei dem vier junge schwarze Mädchen getötet wurden und ein fünftes teilweise erblindete. Sie sagte, das Lied sei, „als würde man zehn Kugeln auf sie zurückwerfen“, und wurde zu einem von vielen weiteren Protestsongs, die Simone schrieb. Das Lied wurde als Single veröffentlicht und in einigen Südstaaten boykottiert.[3][10]

Später erinnerte sie sich daran, dass Mississippi Goddam ihr „erstes Bürgerrechtslied“ war und dass das Lied „in einem Ansturm von Wut, Hass und Entschlossenheit“ zu ihr kam. Das Lied stellte den Glauben in Frage, dass sich die Rassenbeziehungen schrittweise ändern könnten, und forderte sofortige Entwicklungen: „Ich und meine Leute sind jetzt fällig“. Es war ein Schlüsselmoment auf ihrem Weg zum Bürgerrechtsaktivismus.[11] Der Song Old Jim Crow auf demselben Album thematisiert die Jim-Crow-Gesetze zur Verstärkung der Rassentrennung. Nach Mississippi Goddam wurde die Botschaft der Bürgerrechte zur Norm in Simones Aufnahmen und wurde Teil ihrer Konzerte. Als ihr politischer Aktivismus zunahm, verlangsamte sich das Tempo der Veröffentlichung ihrer Musik.

Simone trat auf und sprach bei Bürgerrechtsversammlungen wie den Märschen von Selma nach Montgomery.[12] Wie Malcolm X, ihr Nachbar in Mount Vernon (New York) unterstützte sie den schwarzen Nationalismus und befürwortete eine gewaltsame Revolution anstelle des gewaltlosen Ansatzes von Martin Luther King Jr.[3] Sie hoffte, dass die Afroamerikaner mit Hilfe des bewaffneten Kampfes einen eigenen Staat bilden könnten, obwohl sie in ihrer Autobiografie schrieb, dass sie und ihre Familie alle Rassen als gleichwertig betrachteten.

1974–2003: Späteres Leben

Simone nahm 1974 ihr letztes Album für RCA Records, It Is Finished, auf und nahm erst 1978 wieder eine Platte auf, als sie von Creed Taylor, dem Besitzer von CTI Records, überredet wurde, ins Tonstudio zu gehen. Das Ergebnis war das Album Baltimore, das zwar kein kommerzieller Erfolg war, aber von der Kritik recht gut aufgenommen wurde und eine stille künstlerische Renaissance in Simones Schaffen einläutete.[11] Die Auswahl ihres Materials blieb eklektisch und reichte von geistlichen Liedern bis zu Hall & Oates' Rich Girl. Vier Jahre später nahm Simone Fodder on My Wings bei einem französischen Label, Studio Davout, auf.

Ihr privates Leben war von Krisen geprägt. Sie floh aus ihren Ehen, hatte eine Affäre mit dem Premierminister von Barbados (Errol Barrow), suchte aufgrund einer Empfehlung von Miriam Makeba ihre Bestimmung in Afrika, unternahm Europatourneen, die sie ihrem politischen Kampf in den USA entfremdeten, und galt in der Plattenindustrie zunehmend als schwierig. Ihr Album Baltimore (1978) wurde von der Kritik gelobt, verkaufte sich aber zunächst schlecht. In den 1980ern trat sie regelmäßig im Jazzclub von Ronnie Scott in London auf (und nahm dort auch ein Album auf). Ihre Autobiografie I Put a Spell on You erschien 1992, ihr letztes reguläres Album 1993. Im gleichen Jahr zog sie nach Südfrankreich, wo sie zehn Jahre lebte und 2003 nach langem Krebsleiden starb.

Performance-Stil

Simones Haltung und Bühnenpräsenz brachten ihr den Titel „Hohepriesterin des Soul“ ein. Sie war Pianistin, Sängerin und Performerin, „getrennt und gleichzeitig“.[13] Meist als Arrangeurin und seltener auch als Komponistin bewegte sich Simone vom Gospel über Blues, Jazz und Folk bis hin zu Stücken im Stil der europäischen Klassik. Neben der Verwendung des Bach'schen Kontrapunkts griff sie auf die besondere Virtuosität des romantischen Klavierrepertoires des 19. Jahrhunderts zurück – Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt, Sergei Wassiljewitsch Rachmaninow und andere. Der Jazztrompeter Miles Davis sprach in höchsten Tönen von Simone und zeigte sich tief beeindruckt von ihrer Fähigkeit, einen dreistimmigen Kontrapunkt zu spielen (ihre beiden Hände am Klavier und ihre Stimme liefern jeweils eine separate, aber ergänzende Melodielinie).[6] Auf der Bühne baute sie Monologe und Dialoge mit dem Publikum in ihr Programm ein und nutzte oft die Stille als musikalisches Element.[14] Die meiste Zeit ihres Lebens und ihrer Plattenkarriere wurde sie von dem Schlagzeuger und Jazz-Musiker Leopoldo Fleming und dem Gitarristen und musikalischen Leiter Al Schackman begleitet.[3] Sie war dafür bekannt, dass sie dem Design und der Akustik jedes Veranstaltungsortes große Aufmerksamkeit schenkte und ihre Auftritte auf den jeweiligen Veranstaltungsort abstimmte.[6]

Simone wurde als eine manchmal schwierige oder unberechenbare Künstlerin wahrgenommen, die gelegentlich das Publikum anpöbelte, wenn sie es als respektlos empfand. Schackman versuchte, Simone während dieser Phasen zu beruhigen, indem er solo auftrat, bis sie sich beruhigt hatte und zurückkehrte, um das Konzert zu beenden. Ihre frühen Erfahrungen als klassische Pianistin hatten Simone darauf konditioniert, ein ruhiges, aufmerksames Publikum zu erwarten, und ihre Wut neigte dazu, in Nachtclubs, Lounges oder an anderen Orten, an denen die Gäste weniger aufmerksam waren, aufzuflammen.[6] Schackman beschrieb ihre Live-Auftritte als „hit or miss“ (Treffer oder Niete), die entweder Höhen hypnotischer Brillanz erreichten oder andererseits mechanisch ein paar Songs abspulten und die Konzerte dann abrupt beendeten.

Vermächtnis und Einfluss

Der US-amerikanische Musikkritiker Will Friedwald zitierte sie kurz in seinem Hauptwerk Jazz Singing (1990) und schrieb, dass sie „abweisend und unkommunikativ“ sei und einen Kult betreibe, „den nur ihre Anhänger verstehen“. Inzwischen hat er seine Aussagen 2010 in A biographical guide to the great jazz and pop singers revidiert, ihr einen Artikel gewidmet und ihr die „wichtigste“ Rolle für ihren Einfluss auf den Jazz im 20. Jahrhundert zugeschrieben. Der damalige Präsidentschaftskandidat Barack Obama nannte 2008 Sinner Man einen seiner zehn Lieblingstitel.[15]

Am 28. Mai 2021 veröffentlichten das Montreux Jazz Festival und das Musikunternehmen BMG The Montreux Years. Die in verschiedenen Formaten erhältlichen Live-Alben, darunter Doppel-LP- und Zwei-Disc-CD-Editionen, bieten eine Sammlung der besten Auftritte von Nina Simone beim Montreux Jazz Festival, darunter auch bisher noch nie veröffentlichtes Material, das in seiner vollen Klangqualität restauriert wurde.

Populärkultur

Der Titel Ain't Got No / I Got Life von ihrem 1968er-Album ’Nuff Said! ist ein Medley aus zwei Songs aus dem Musical Hair. Einem größeren Publikum bekannt wurde sie vor allem durch ihren Song My Baby Just Cares for Me, der 1987 dank einem Chanel-Werbespot, 30 Jahre nach der Aufnahme des Stücks, ein Welthit wurde. An den Verkaufserlösen war sie nur minimal beteiligt. 1993 kam der Film Codename: Nina mit Bridget Fonda in der Hauptrolle in die Kinos – mit einem Soundtrack, der teilweise aus Musik von Nina Simone bestand. In dem 1999er-Remake von Thomas Crown ist nicht zu fassen mit Pierce Brosnan und Rene Russo taucht das Intro ihrer Version des Gospels Sinnerman immer wieder auf, um schließlich den Höhepunkt des Films mit ihrem unverwechselbaren Gesang zu unterlegen.[16] 2009 nutzte Pandemic Studios Simones Version des Lieds Feeling Good sowie eine Remix-Version als musikalische Untermalung des im Paris des Zweiten Weltkriegs spielenden Computerspiels Saboteur.[17] Dieser Song wurde auch als Sample für New Day von Kanye West und Jay-Z auf deren Kollaborationsalbum Watch the Throne.

Im Dezember 2017 wurde Simone postum mit der Aufnahme in die Rock and Roll Hall of Fame geehrt. Die offizielle Zeremonie fand im April 2018 statt. Die Laudatio hielt Mary J. Blige.[18][19]

Filme

Der französische Dokumentarfilm Nina Simone: La Légende wurde in den 1990er-Jahren von dem französischen Filmemacher Frank Lords[20] gedreht. Er basiert auf der Autobiografie I Put a Spell on You und zeigt mehrere Sequenzen aus verschiedenen Phasen der Karriere der Sängerin, Interviews mit Freunden und der Familie sowie mit Nina Simone selbst während ihres Umzugs in die Niederlande und während einer Reise zu ihrem Geburtsort. Einige Szenen des Dokumentarfilms stammen aus einem 26-minütigen biografischen Dokument, das zuvor von Peter Rodis gedreht und 1969 unter dem Titel Einfach Nina[21] veröffentlicht wurde.

Ihr Auftritt beim Montreux Jazz Festival 1976 ist als Video bei Eagle Rock Entertainment erhältlich (Nina Simone: Live at Montreux 1976. Dokumentarfilm. Regie: Jean Bovon, Arte, Schweiz, Großbritannien 1976). Der Film wird jedes Jahr in New York bei der Veranstaltung „The Rise and Fall of Nina Simone: Montreux, 1976“ gezeigt, die von Tom Blunt organisiert wird.

Unter der Regie von Liz Garbus wurde 2015 der Dokumentarfilm What Happened, Miss Simone? gedreht. Ausführende Produzentin war die Tochter von Lisa Simone, die Simones Nachlass verwendete. Der Film wurde als Gegenstück zu dem nicht autorisierten Film von Cynthia Mort (Nina, 2016) produziert und enthielt bisher unveröffentlichtes Archivmaterial. Premiere des Films war auf dem Sundance Film Festival im Januar 2015. Am 26. Juni 2015 wurde er von Netflix veröffentlicht.[22] Die Veröffentlichung von Nina war für Dezember 2015 geplant[23] wurde aber erst am 22. April 2016 in einer begrenzten Auflage und als Video-on-Demand veröffentlicht.[24]

Einen Teil ihres Lebens behandelt der Spielfilm Nina mit Zoe Saldana in der Hauptrolle, der im April 2016 veröffentlicht wurde. Der Film löste Diskussionen zur Frage aus, ob Saldana – als Amerikanerin mit dominikanischen Wurzeln – für die Verkörperung einer Afroamerikanerin geeignet sei.[25]

Ehrungen

Der Rolling Stone listete Simone 2008 auf Rang 29 der 100 größten Sänger aller Zeiten.[26]

Im Jahr 2002 benannte die Stadt Nijmegen (Niederlande) eine Straße nach ihr, die „Nina-Simone-Straße“: Sie hatte zwischen 1988 und 1990 in Nijmegen gelebt. Am 29. August 2005 ehrten die Stadt Nimwegen, die Konzerthalle De Vereeniging und mehr als 50 Künstler (darunter Frank Boeijen, Rood Adeo und Fay Claassen)[27] Simone mit dem Tribute-Konzert Greetings from Nijmegen.

2004 begann Angélique Kidjo als Hommage an Nina Simone mit Lizz Wright und Dianne Reeves das Projekt Sing the Truth. Unter der künstlerischen Leitung der Schlagzeugerin Terri Lyne Carrington widmen sich die Musikerinnen dem Werk engagierter Frauen wie Odetta, Billie Holiday, Miriam Makeba und anderen.[28]

Die 2008 von der deutschen Jazzsängerin Lyambiko veröffentlichte CD Saffronia (Sony BMG) ist eine Hommage an Nina Simone.

Simone wurde 2009 in die North Carolina Music Hall of Fame aufgenommen.[29]

Die amerikanische Funk- und Jazz-Sängerin Meshell Ndegeocello veröffentlichte 2012 ihr eigenes Tribute-Album Pour une Âme Souveraine (deutsch:Für eine Souveräne Seele): A Dedication to Nina Simone im Jahr 2012.

2013 veröffentlichte anschließend die US-amerikanische experimentelle Independent-Rock-Band Xiu Xiu ein Coveralbum, Nina.

Im Dezember 2017 wurde Simone postum mit der Aufnahme in die Rock and Roll Hall of Fame geehrt. Die offizielle Zeremonie fand im April 2018 statt. Die Laudatio hielt Mary J. Blige.[30][31][32]

Bei den Proms wurde Nina Simone 2019 eine Hommage gewidmet: Das Metropole Orkest unter der Leitung von Jules Buckley spielte in der Royal Albert Hall das Stück Mississippi Goddamn. Ledisi, Lisa Fischer und Jazz-Trio, LaSharVu sorgten für den Gesang.[33][34]

Am 11. Mai 2019 wird am Rande des Konzerts, das ihre Tochter Lisa Simone im Rahmen des Jazzfestivals im Theater von Longjumeau gibt, in Anwesenheit ihrer Tochter und ihrer Enkelin Rihanna eine Nina-Simone-Allee eingeweiht, die zum Auditorium des Theaters führt.[35] Auch in Heidelberg wurde 2018 im ehemaligen US-Hauptquartier eine Straße nach ihr benannt.[36]

Diskografie

Nina Simone konnte seit ihrem Karrierebeginn 1959 über fünf Jahrzehnte Alben und Singles in den Charts platzieren. Noch nach ihrem Tod 2003 erreichten postume Veröffentlichungen die Charts. Aufgeführt sind jeweils nur Platzierungen in den Hauptcharts. Auch in den genrespezifischen Jazz-, Adult-Contemporary- und Black-Music-Charts verschiedener Länder war Simone vertreten. Gemäß Quellenangaben und Schallplattenauszeichnungen hat sie bisher mehr als 2,5 Millionen Tonträger verkauft. Die erfolgreichste Veröffentlichung von Simone ist das Album The Very Best of mit über 600.000 verkauften Einheiten. Zu Details über die Diskografie siehe Nina Simone Diskografie.

Chartplatzierungen von Studioalben

- 1958: Little Girl Blue

| Jahr | Titel | Höchstplatzierung, Gesamtwochen, AuszeichnungChartplatzierungenChartplatzierungen[37] (Jahr, Titel, Platzierungen, Wochen, Auszeichnungen, Anmerkungen) | Anmerkungen | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Little Girl Blue auch bekannt als: My Baby Just Cares for Me | DE46a (4 Wo.)DE | AT4a (12 Wo.)AT | CH21a (4 Wo.)CH | UK56a (8 Wo.)UK | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 24. Juni 1958, spätere Neuveröffentlichung als Jazz as Played in an Exclusive Side Street Club |

| 1965 | Pastel Blues | — | — | — | — | US139 (7 Wo.)US |

Erstveröffentlichung: 1965 |

| I Put a Spell on You | — | — | — | UK18 (3 Wo.)UK | US99 (8 Wo.)US |

Erstveröffentlichung: Juni 1965 | |

| 1966 | Wild Is the Wind | — | — | — | — | US110 (9 Wo.)US |

Erstveröffentlichung: 1966 |

| 1967 | Silk & Soul | — | — | — | — | US158 (4 Wo.)US |

Erstveröffentlichung: Oktober 1967 |

| 1969 | ’Nuff Said! | — | — | — | UK11 (1 Wo.)UK | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: Februar 1968 teilweise Live-/Studioalbum |

| 1971 | Here Comes the Sun | — | — | — | — | US190 (4 Wo.)US |

Erstveröffentlichung: 1971 |

| 2020 | Fodder on My Wings | — | AT57 (1 Wo.)AT | — | — | — |

Neuauflage, Erstveröffentlichung: 1982 (Frankreich) |

grau schraffiert: keine Chartdaten aus diesem Jahr verfügbar

Literatur

- Nina Simone, Stephen Cleary: I Put a Spell on You. The Autobiography of Nina Simone. Ebury Press, London 1991, ISBN 0-85223-895-9.

- Meine schwarze Seele. Erinnerungen. Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-455-08481-8 (aus dem Amerikanischen von Brigitte Jakobeit).

- Richard Williams: Nina Simone: Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood. Canongate, Edinburgh 2002, ISBN 978-1-841-95368-7.

- Kerry Acker: Nina Simone. Chelsea House, Philadelphia 2004, ISBN 978-0-791-07456-5.

- Sylvia Hampton, David Nathan: Nina Simone: Break Down and Let It All Out. Sanctuary, London 2004, ISBN 1-86074-552-0.

- Andrew Stroud: Nina Simone „Black is the Color ...“. Xlibris, Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 1-599-26670-9.

- Alan Light: What Happened, Miss Simone? Crown Archetype, New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-101-90487-9.

- Nadine Cohodas: Princess Noire. The tumultuous reign of Nina Simone. Pantheon Books, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-375-42401-4.

- Traci N. Todd: Nina: A Story of Nina Simone. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York 2021, ISBN 978-1-5247-3728-3 (illustriert von Christian Robinson, Zielgruppe Kinder bis 11 Jahre).

Weblinks

- Literatur von und über Nina Simone im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

- Porträt (Bayerischer Rundfunk)

- Biografie in „Jazz Echo“, hrsg. von Universal Music

- Biografie mit kompletter Songliste (englisch)

- Nina Simone bei IMDb

- Nina Simone bei Discogs

- Jazz Legende Nina Simone live im Ronnie Scotts Jazz Club (1985)

- Jazz-Ikone Nina Simone – Mit Musik gegen Rassismus, SWR2 Wissen 21.04.2023

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Nina Simone. Abgerufen am 16. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Nadine Cohodas: Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. Pantheon Books, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-375-42401-4 (englisch).

- ↑ a b c d e Nina Simone, Stephen Cleary: I Put a Spell on You. Da Capo Press, New York 1992, ISBN 0-306-80525-1 (englisch, Vorwort von Dave Marsh in der zweiten Auflage).

- ↑ Adam Shatz: The Fierce Courage of Nina Simone - She did not so much interpret songs as take possession of them. In: nybooks.com. The New York Review, 10. März 2016, abgerufen am 15. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ a b Obituaries: Nellie Lutcher. 11 June 2007. Archiviert vom Original am 6. August 2011; abgerufen am 26. Mai 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Alan Light: What Happened, Miss Simone? A Biography. Crown Archetype, 2016, ISBN 978-1-101-90487-9 (englisch).

- ↑ "Curtis Institute and the case of Nina Simone" archivierte Version des Artikels von Peter Dobrin, erschienen am 16. August 2015 im Philadelphia Inquirer

- ↑ Nina Simone Foundation. In: web.archive.org. Nina Simone Foundation, archiviert vom Original am 19. Juni 2008; abgerufen am 11. Dezember 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Ulrich Biermann und Veronika Bock: 29. Februar 1964 – Nina Simones „Mississippi Goddam“ uraufgeführt (im Februar 1964) In: WDR5, ZeitZeichen, 29. Februar 2024, (Podcast, 14:41 Min., verfügbar bis 1. März 2099).

- ↑ Mark Anthony Neal: Nina Simone: She Cast a Spell —and Made a Choice. 4. Juni 2003, archiviert vom Original am 15. Juli 2007; abgerufen am 12. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ a b Ruth Feldstein: I Don't Trust You Anymore: Nina Simone, Culture, and Black Activism in the 1960s. In: The Journal of American History. Band 4, Nr. 91, 2005, S. 1349–1379 (englisch).

- ↑ Nina Simone Database. Timeline. In: boscarol.com. Abgerufen am 12. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Nina Simone, high priestess of soul, dies aged 70. Abgerufen am 11. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Biography, By Roger Nupie, President “International Dr. Nina Simone Fan Club”, da http://www.ninasimone.com/. In: fornina.com. 9. Mai 2010, abgerufen am 11. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Nina Simone, une voix se lève. In: vanityfair.fr. 25. Dezember 2014, abgerufen am 15. Oktober 2022 (französisch).

- ↑ Auch der 2004 erschienene Film Final Call – Wenn er auflegt, muss sie sterben sowie die Neuverfilmung der Actionserie Miami Vice von 2006 hatten eine Variante von Simones Sinnerman als Titelsong. In der BBC-Serie Sherlock war in der dritten Folge der zweiten Staffel („Sherlock – Der Reichenbachfall“) ebenfalls ihre Version von Sinnerman zu hören. Das Lied läuft in voller Länge im Abspann von Golden Door von 2006.

- ↑ Videogamer.com: The Saboteur Review. 3. Dezember 2009, archiviert vom Original am 22. Oktober 2012; abgerufen am 6. November 2010.

- ↑ Read Mary J. Blige's Heartfelt Nina Simone Rock Hall Induction Speech. In: Rolling Stone. 15. April 2018, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2021 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Bon Jovi in der Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: „Ein frühes Anzeichen der Zombie-Apokalypse“. In: RP Online. 15. April 2018, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2021.

- ↑ Nina Simone: La légende. In: imdb.com. 1992, abgerufen am 12. Oktober 2022 (französisch).

- ↑ Peter Rodis: Nina Simone - A Historical Perspective by Peter Rodis. In: vimeo.com. 1970, abgerufen am 12. Oktober 2022 (englisch, französisch).

- ↑ Review: 'What Happened, Miss Simone' Leaves Us Wondering What Happens When What You Love Most, Haunts You. In: shadowandact.com. 23. Juni 2015, abgerufen am 10. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Zoe Saldana’s ‘Nina’ Bought by RLJE, Set for December Release (EXCLUSIVE). In: variety.com. 10. September 2015, abgerufen am 4. November 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Watch: Trailer for Nina Simone Biopic Starring Zoe Saldana Arrives. In: web.archive.org. 2. März 2016, archiviert vom Original am 7. März 2016; abgerufen am 4. November 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Zoë Saldanas umstrittene Rolle – „Für eine schlechte Halloween-Party angemalt“. In: Spiegel Online. 2. März 2016, abgerufen am 4. März 2016.

- ↑ 100 Greatest Singers of All Time. Rolling Stone, 2. Dezember 2010, abgerufen am 9. August 2017 (englisch).

- ↑ Klaas-Jan Grafe: Nina Simone krijgt indrukwekkende ode - Zangeres is wel te eren, maar niet te imiteren. In: 3voor12.vpro.nl. 30. November 2005, abgerufen am 10. Oktober 2022 (niederländisch).

- ↑ Programmheft zum Rudolstadt-Festival 2019, S. 102

- ↑ Music Hall of Fame - Nina Simone. In: northcarolinamusichalloffame.org. Abgerufen am 10. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Read Mary J. Blige’s Heartfelt Nina Simone Rock Hall Induction Speech. In: Rolling Stone. 15. April 2018, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2021 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Bon Jovi in der Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: „Ein frühes Anzeichen der Zombie-Apokalypse“. In: RP Online. 15. April 2018, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2021.

- ↑ Erika Harwood: The Irony of Nina Simone Joining the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame - Her class includes Bon Jovi, the Cars, and more, but Simone herself knew she belonged to a class of her own. In: vanityfair.com. 13. Dezember 2017, abgerufen am 10. Oktober 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Rachel Coombes: Mississippi Goddam: The 2019 Nina Simone Prom at the Royal Albert Hall. In: London Jazz News. 23. August 2019, abgerufen am 5. November 2019.

- ↑ Homage to Nina Simone. In: BBC Radio 3. 2019, abgerufen am 5. November 2019.

- ↑ Longjumeau inaugure une allée « Nina Simone » en présence de sa fille et sa petite-fille - La mairie rend hommage à une « très grande artiste du XXe siècle ». La cérémonie s’est déroulée en marge du festival de jazz où Lisa Simone était tête d’affiche ce samedi. In: leparisien.fr. LeParisien, 11. Mai 2019, abgerufen am 12. Oktober 2022 (französisch).

- ↑ Nina-Simone-Straße. Abgerufen am 25. November 2023.

- ↑ Chartquellen: DE AT CH UK US US (vor 17. August 1963)

| Personendaten | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Simone, Nina |

| ALTERNATIVNAMEN | Waymon, Eunice Kathleen (Geburtsname) |

| KURZBESCHREIBUNG | US-amerikanische Musikerin, Jazz- und Bluessängerin, Pianistin und Songschreiberin |

| GEBURTSDATUM | 21. Februar 1933 |

| GEBURTSORT | Tryon, North Carolina, USA |

| STERBEDATUM | 21. April 2003 |

| STERBEORT | Carry-le-Rouet, Frankreich |