Artist(s)

Veröffentlichungen von Taylor Swift die im OTRS erhältlich sind/waren:

Folklore ¦ Evermore ¦ Fearless (Taylor’s Version) ¦ 1989 ¦ Red (Taylor's Version) ¦ Lover ¦ Reputation ¦ Midnights ¦ Taylor Swift ¦ Red ¦ 1989 (Taylor's Version) ¦ Speak Now (Taylor's Version) ¦ Speak Now

Taylor Swift auf Wikipedia (oder andere Quellen):

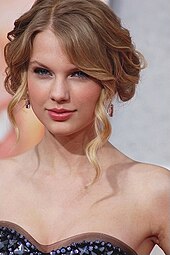

Taylor Alison Swift (* 13. Dezember 1989 in Reading, Pennsylvania) ist eine US-amerikanische Pop- und Country-Sängerin, Gitarristin, Songwriterin, Musikproduzentin und Schauspielerin. Sie hat laut IFPI mehr als 300 Millionen Tonträger verkauft (Stand: August 2023) und gehört damit zu den weltweit erfolgreichsten Künstlern.[1]

Swift begann im Alter von 14 Jahren mit dem Schreiben von Texten. Dafür, und um Country-Musikerin zu werden, zog sie im selben Alter nach Nashville. 2004 unterzeichnete sie einen Songwriting-Vertrag bei Sony/ATV Music Publishing und 2005 einen Plattenvertrag bei Big Machine Records. Ihr Debütalbum Taylor Swift machte sie 2006 zur ersten Country-Sängerin, die an einem mit Platin ausgezeichneten US-Album mitgeschrieben hat.

Swifts nächste Alben, Fearless (2008) und Speak Now (2010), waren im Country-Pop angesiedelt, wobei auf dem Album Speak Now auch Rockelemente erkennbar sind. Die in Fearless enthaltenen Love Story und You Belong with Me waren die ersten Country-Songs, die die US-Pop- bzw. All-Genre-Airplay-Charts anführten und machten Swift schlagartig berühmt. Mit dem 2012 erschienenen Album Red, das ihren ersten Nummer-eins-Song der Billboard Hot 100, We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together, enthielt, experimentierte sie mit elektronischen Stilen.

Mit ihrem 2014 veröffentlichten fünften Studioalbum 1989 hatte sie das Country-Genre gänzlich verlassen; die darin enthaltenen Synthiepop-Lieder Shake It Off, Blank Space und Bad Blood wurden Chartstürmer. Die Aufmerksamkeit der Medien inspirierte ihr Hip-Hop-geprägtes Album Reputation (2017), aus dem die Nummer-eins-Single Look What You Made Me Do hervorging. Swift verließ den Musikverlag Big Machine, unterschrieb 2018 bei Republic Records und veröffentlichte 2019 ihr siebtes Studioalbum Lover, gefolgt von der im Jahr darauf erschienenen autobiografischen Dokumentation Miss Americana. Während der COVID-19-Pandemie veröffentlichte Swift die Indie-Folk- und Alternative-Rock-Alben Folklore und Evermore, deren Lead-Singles Cardigan und Willow die Hot 100 anführten.

Nach einem Streit mit Big Machine Records nahm sie ihre bei jenem Musikverlag erschienenen sechs Alben neu auf und veröffentlichte die ersten vier von ihnen unter den Namen Taylor’s Versions in den Jahren 2021 bis 2023. Dabei wurde ihre überarbeitete Version von All Too Well mit einer Dauer von 10:13 Minuten zum längsten Nummer-1-Hit der Hot-100-Chartgeschichte. Ihr zehntes Studioalbum, Midnights, erschienen 2022, brach mehrere Streaming-Rekorde und war ihr fünftes Album, das sich in den USA über eine Million Mal verkaufte, was keiner Musikerin zuvor gelang. Dieses Chill-out-Album enthält ihren neunten Nummer-eins-Hit Anti-Hero. Swift hat bei den Musikfilmen Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions und All Too Well: The Short Film Regie geführt und in anderen Filmen Nebenrollen gespielt.

Mit weltweit über 200 Millionen verkauften Platten ihrer Diskografie gehört Swift zu den kommerziell erfolgreichsten Musikern aller Zeiten. Sie löste Barbra Streisand mit zwölf Nummer-eins-Alben als in dieser Hinsicht führende Künstlerin ab und brach den von Elvis Presley gehaltenen Rekord, die längste Zeit als Solokünstler die Billboard-Albumcharts anzuführen. Zudem ist sie die erste Künstlerin, die gleichzeitig alle zehn Plätze der Top Ten der amerikanischen Singlecharts besetzte. Insgesamt erzielte Swift in ihrem Heimatland elf Nummer-eins-Singles und dreizehn Nummer-eins-Alben. Swift hält mehr als 100 Guinness-Weltrekorde und ist die am meisten gestreamte Frau auf Spotify. Zu Swifts Auszeichnungen zählen 14 Grammy Awards, darunter vier für das Album des Jahres[2], 40 American Music Awards (was keinem anderen Interpreten gelang[3]), 29 Billboard Music Awards (die meisten für eine Sängerin), 23 MTV Video Music Awards und ein Emmy Award. Sie ist in Rankings wie Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time, Billboard’s Greatest of All Time Artists, The Time 100 und Forbes Celebrity 100 vertreten und wurde im Jahr 2023 von der Zeitschrift Time zur Person of the Year gekürt. Ihrer Musik wird zugeschrieben, eine Generation von Singer-Songwritern beeinflusst zu haben. Swift ist eine Fürsprecherin für Künstlerrechte und Frauenförderung.

Leben

Taylor Swift wurde 1989 in Reading, Pennsylvania in eine Familie der oberen Mittelschicht aus Wyomissing geboren.[4] Sie wurde nach dem US-amerikanischen Musiker James Taylor benannt, mit dem sie auch schon gemeinsam musiziert hat.[5] Ihre Mutter Andrea Gardner Finlay war zunächst leitende Angestellte im Marketingbereich und später Hausfrau. Ihr Vater Scott Kingsley Swift ist Vermögensberater bei Merrill Lynch.[6] Ihr jüngerer Bruder ist der Schauspieler Austin Swift. Swifts Eltern betrieben auch eine Baumschule für Weihnachtsbäume.[7]

Ihre Großmutter mütterlicherseits, Marjorie Finlay, war Opernsängerin und inspirierte Swift schon in ihrer frühen musikalischen Karriere.[8][9] Swift widmete ihr auf ihrem neunten Studioalbum – evermore – das Lied marjorie. Auf dem vorherigen Album folklore sang sie in epiphany unter anderem über die Kriegstraumata ihres Großvaters Dean, der im Zweiten Weltkrieg im Kampf gegen Japan eingesetzt worden war.

Swift besuchte den Kindergarten und die Vorschule der Alvernia Montessori School, bis sie zur The Wyndcroft School in Pottstown wechselte.[10] Als ihre Familie in eine Vorstadt von Wyomissing zog, ging sie zur Wyomissing Area Junior/Senior High School.[11] Später zog ihre Familie nach Hendersonville in Tennessee, um näher an Nashville, dem Zentrum der Country-Musik, zu sein.[12] Dort besuchte sie die Hendersonville High School. Mit 15 Jahren wechselte sie in den Fernunterricht und erhielt so ihren Schulabschluss.[13]

Swift hörte in ihrer Kindheit besonders Country-Musik von Künstlerinnen wie LeAnn Rimes, Patsy Cline, Dolly Parton, den Dixie Chicks und Shania Twain. Im Alter von neun Jahren nahm sie Musik- und Gesangsunterrichtsstunden in New York City. Mit zehn Jahren begann Swift an Karaokewettbewerben teilzunehmen und bei Festivals und Messen als Sängerin aufzutreten. Dafür schrieb sie bereits eigene Songs. Mit elf Jahren versuchte sie, in Nashville bei verschiedenen Plattenlabels einen Vertrag zu erhalten. Mit zwölf Jahren lernte sie, Gitarre zu spielen.[14]

Nach zahlreichen Besuchen in Nashville gelang es ihr, einen Development Deal bei RCA Records zu erwerben. Mit 14 Jahren unterschrieb sie einen Vertrag bei Sony/ATV als Songwriterin und wurde später bei einem Auftritt im Bluebird Café von Scott Borchetta entdeckt, der sie für sein neues Plattenlabel Big Machine Records verpflichtete.[15] 2010 war Swift, nach den Dreharbeiten von Valentinstag, für einige Monate mit Taylor Lautner liiert.[16] 2015 bis 2016 führte Swift eine Beziehung mit Calvin Harris. Sie schrieb seinen Song This Is What You Came For unter dem Pseudonym Nils Sjöberg.[17] Ab 2016 war sie mit dem britischen Schauspieler Joe Alwyn zusammen, laut Medien soll sich das Paar 2023 getrennt haben.[18][19] Im Mai 2022 wurde Swift die Ehrendoktorwürde der New York University (NYU) verliehen.[20] Seit 2023 ist sie mit Travis Kelce, einem Football-Spieler und dreifachen Super-Bowl-Sieger der Kansas City Chiefs, liiert.[21]

Künstlerischer Werdegang

2006–2012: Taylor Swift, Fearless, Speak Now und Red – Anfänge mit Country

2006 veröffentlichte Swift ihre Debütsingle Tim McGraw, die Platz sechs in den amerikanischen Country-Charts erreichte.[22] Ihr Debütalbum Taylor Swift wurde im Oktober desselben Jahres veröffentlicht und belegte Platz fünf der Billboard 200. Es wurde von der RIAA mit Fünffach-Platin ausgezeichnet. Aus dem Album erreichten vier Singles die Top Ten der US-Country-Charts; in den Billboard Hot 100 kamen drei der Singles in die Top 40. Alle Songs auf diesem Album hat Swift entweder selbst geschrieben oder sie wurden von ihr mitverfasst. Im November 2008 veröffentlichte sie ihr zweites Album Fearless, das die Albumcharts mit Unterbrechungen elf Wochen lang anführte.[23] Kein anderes Album seit dem Jahr 2000 konnte diesen Spitzenplatz länger behaupten, und es war in den Vereinigten Staaten das meistverkaufte Album des Jahres 2009.[24] Anfang Februar 2009 wurde die Single Love Story aus dem Album Fearless mit rund 2,7 Millionen Einheiten zum Country-Song mit den meisten bezahlten Downloads.[25] Im September 2009 konnte ihr Titel You Belong with Me den ersten Platz der Country-Charts erreichen.

2010 gewann sie den People’s Choice Award in der Kategorie Beste Künstlerin.[26] Bei den Grammy Awards 2010 erhielt sie vier Auszeichnungen. Im Februar 2010 führte ihre Fearless Tour durch fünf Städte Australiens, bei der die Country-Band Gloriana im Vorprogramm auftrat.[27] Swifts drittes Album Speak Now, das im Oktober 2010 veröffentlicht wurde, verkaufte sich in den USA innerhalb der ersten Woche mehr als eine Million Mal. Die Songs des Albums entstanden in Arkansas, New York City, Boston und Nashville und wurden von ihr selbst geschrieben. Als Co-Produzent trat Nathan Chapman auf, der bereits an Swifts ersten beiden Alben mitgewirkt hatte. Die erste Singleauskopplung des Albums war Mine; es folgten Back to December, Mean, The Story of Us, Sparks Fly und Ours. Für Mean wurde sie mit zwei Grammys ausgezeichnet.[28]

Ihr viertes Studioalbum Red erschien im Oktober 2012 und wurde von Nathan Chapman produziert. Die erste Single aus diesem Album war We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together, die zum ersten Nummer-eins-Hit für Swift in den USA wurde.[29] Als zweite Single wurde Begin Again veröffentlicht. Die dritte Single I Knew You Were Trouble konnte sich in Deutschland in den Top 10 platzieren, in Großbritannien und in den USA erreichte sie Platz zwei. Die Single verkaufte sich in den USA mehr als drei Millionen Mal.[30] Als vierte Singleauskopplung folgte 22. Das Album verkaufte sich mehr als sechs Millionen Mal. Swift, die 2011 mit Einnahmen von über 35 Millionen US-Dollar weltweit die kommerziell erfolgreichste Musikerin war,[31] spielt eine akustische Westerngitarre der kalifornischen Firma Taylor Guitars aus dem Holz der Koa-Akazie.[32]

2014–2019: 1989, Reputation und Lover – Wechsel zur Popmusik

Im Oktober 2014 veröffentlichte Universal Music ihr fünftes Studioalbum mit dem Titel 1989, das sie unter anderem zusammen mit Max Martin, Shellback, Ryan Tedder, Jack Antonoff, Nathan Chapman, Imogen Heap und Greg Kurstin wieder bei Big Machine Records produziert hatte.[33] Der Name des Albums bezieht sich auf Swifts Geburtsjahr. Mit dem Album wandte sich die Sängerin erstmals von Country in Richtung Pop. Einen ersten Ausblick auf die neue Stilrichtung des Albums gab sie im August 2014 mit der Veröffentlichung der Single Shake It Off und im Rahmen eines Live-Streaming-Events aus New York City und der Veröffentlichung des Musikvideos zur Single. Diese wurde zu Swifts zweitem US-Nummer-eins-Hit.[34] Die zweite Single Blank Space wurde im November als Musikdownload und in Deutschland im Januar 2015 als CD veröffentlicht; es gelang der Künstlerin zum dritten Mal der Sprung an die Spitze der US-amerikanischen Charts. Als weitere Singles des Albums wurden im Februar Style, im Mai Bad Blood und im August Wildest Dreams ausgekoppelt. Bad Blood avancierte dabei in einer zusammen mit Rapper Kendrick Lamar vorgetragenen Version zu Swifts viertem Nummer-eins-Hit. Im Januar 2016 wurde Out of the Woods und im Februar New Romantics als Single ausgekoppelt.

Ihr sechstes Studioalbum Reputation erschien im November 2017.[35] Die erste Singleauskopplung Look What You Made Me Do wurde vorab im August 2017 veröffentlicht und stieg in die Top 10 der deutschen, österreichischen und Schweizer Singlecharts ein. In den britischen Singlecharts und in den Billboard Hot 100 gelang ihr mit diesem Song ein Nummer-eins-Erfolg. Als zweite Auskopplung folgte …Ready for It? Swift fungierte zusammen mit Jack Antonoff, Max Martin und Shellback als Produzentin. In dem Song End Game kollaborierte sie mit dem Rapper Future und dem Sänger Ed Sheeran.[36]

Auf der Tour zu ihrem sechsten Studioalbum Reputation, der Reputation Stadium Tour, spielte sie 345,5 Millionen US-Dollar ein und hatte während ihren 53 Shows 2,88 Millionen Zuschauer. Die Tour erzielte den Rekord für die höchsten Einnahmen einer US-Tour.[37]

Nachdem Swift ME! (feat. Brendon Urie) als erste Vorab-Singleauskopplung von ihrem siebten Studioalbum Lover im April 2019 veröffentlicht hatte, zeigte sie mit der zweiten Vorab-Singleauskopplung You Need to Calm Down ihre Unterstützung für die LGBT-Community. Das Lied wurde dazu passend während des Pride Months veröffentlicht. In dem Musikvideo traten Prominente wie Katy Perry, Ellen DeGeneres und Adam Lambert auf.[38] Das zugehörige Studioalbum – veröffentlicht durch Republic Records – erschien nach der Veröffentlichung der Promo-Singleauskopplung The Archer und der dritten Vorab-Singleauskopplung Lover im August 2019. Nach der Veröffentlichung des Albums wurde The Man als vierte und vorerst letzte Singleauskopplung im Frühjahr 2020 veröffentlicht. Im zugehörigen Musikvideo spielte Swift die im Lied beschriebene Identität Swifts als Mann.

2020: Folklore und Evermore – Neuausrichtung zu Indie und Folk

Wegen der COVID-19-Pandemie wurden Swifts Auftritte in den Vereinigten Staaten und Brasilien bis 2021 verschoben.[39] Im Mai 2020 wurden Aufnahmen von ihrem City-of-Lover-Konzert aus dem Jahr 2019 auf ABC ausgestrahlt. Sie veröffentlichte auch die Liveversionen der Lover-Lieder, die sie bei diesem Konzert gesungen hatte.[40] Im Juni 2020 wirkte sie bei YouTubes Livestream Dear Class of 2020 mit.[41][42]

Im Juli 2020 erschien ihr achtes Studioalbum Folklore.[43] Damit und mit der Single Cardigan war sie die erste Künstlerin, die in derselben Woche auf Rang eins der Billboard 200 und der Hot 100 einsteigen konnte.[44] Im März 2021 gewann sie mit Folklore die Auszeichnung Album of the Year bei den Grammy Awards.[45]

2020 wurde nach der Premiere beim Sundance Festival auf Netflix die Dokumentation Taylor Swift: Miss Americana (Miss Americana) veröffentlicht.[46]

Im Dezember 2020 erschien mit Evermore ihr neuntes Studioalbum. Ebenso wie beim Vorgängeralbum hatte sie alle Songs während der Covid-19-Pandemie in Selbstisolation geschrieben. Bereits zum zweiten Mal gelang es ihr, mit einem Album und einer Single gleichzeitig auf Platz 1 der US-Charts zu debütieren; der Song Willow positionierte sich ebenso wie das Album umgehend an der Chartspitze.[47]

Seit 2021: Neueinspielung der Alben bei Big Machine Records

Im April 2021 veröffentlichte Swift eine Neueinspielung ihres Albums Fearless (mit dem Zusatz Taylor’s Version), um auf diese Weise die kommerzielle Verfügungsgewalt über ihre Kompositionen zurückzugewinnen. Die „perfekt wirkende Eins-zu-eins-Kopie“ bezeichnet Andreas Borcholte deshalb als einen „Akt der künstlerischen Selbstermächtigung“.[48] Zusätzlich zu den Neuaufnahmen ursprünglicher Songs, wurden unter Fearless (Taylor’s Version) sechs weitere Songs veröffentlicht. Bei diesen Songs – gekennzeichnet mit From The Vault – handelt es sich um Werke, welche es aus verschiedenen Gründen nicht in das damalige Fearless-Album geschafft hatten.[49] In einem öffentlichen Brief erklärt Swift ihre Intention folgendermaßen:

“I’ve spoken a lot about why I’m remaking my first six albums, but the way I’ve chosen to do this will hopefully illuminate where I’m coming from. Artists should own their own work for so many reasons, but the most screamingly obvious one is that the artist is the only one who really *knows* that body of work.”

„Ich habe schon oft darüber gesprochen, warum ich meine ersten sechs Alben neu aufnehme, aber die Art und Weise, wie ich dies tue, wird hoffentlich verdeutlichen, warum ich es tue. Künstler sollten aus vielen Gründen ihr eigenes Werk besitzen, aber der offensichtlichste Grund ist, dass der Künstler der Einzige ist, der das Werk wirklich kennt.“

Red (Taylor’s Version) wurde im November 2021 mit 30 Songs – anstelle der ursprünglichen 19 Songs aus Red – veröffentlicht.[51] Zusammen mit einer überarbeiteten Version des Liedes All Too Well konnte Swift erneut zeitgleich in derselben Woche mit einem Song und einem Album an der Spitze der US-Charts einsteigen. Mit der zehnminütigen Version von All Too Well brach Swift den vorherigen Rekord (gehalten von Don McLean mit American Pie) für das längste Lied, welches es auf den ersten Platz der Billboard Hot 100 schaffte.[52] Zudem erschien ein zugehöriger Kurzfilm mit dem Titel All Too Well: The Short Film, mit welchem Swift bei den MTV Video Music Awards 2022 in den Rubriken Video of the Year, Best Longform Video und Best Direction gewann.[53]

Im Juli 2023 veröffentlichte Swift die Neuaufnahme ihres Albums Speak Now (Speak Now (Taylor’s Version)). In den zuvor unveröffentlichten From The Vault-Tracks Castles Crumbling und Electric Touch kollaborierte Swift gesanglich mit Hayley Williams, beziehungsweise Fall Out Boy.[54] Am Folgetag wurde ein Musikvideo zu I Can See You auf der parallel laufenden The Eras Tour uraufgeführt, für welches die US-amerikanischen Schauspieler Taylor Lautner, Joey King, Presley Cash und Swift persönlich, die auch eigenständig Regie führte, Teil der Besetzung waren.[55]

Im August 2023 kündigte Swift während eines Auftritts die Veröffentlichung von 1989 (Taylor’s Version) für den 27. Oktober 2023 an.[56]

Seit 2022: Midnights – Rückkehr zur Popmusik

Ihr zehntes Studioalbum Midnights erschien im Oktober 2022. Das Album enthält dreizehn Songs über schlaflose Nächte.[57] Es hatte den besten Verkaufsstart in den USA seit 2017 und konnte in seiner ersten Woche über eine Million Verkäufe in den USA verzeichnen. Bei Charteintritt konnte Swift als erste Interpretin alle zehn Plätze der US-amerikanischen Top Ten der Singlecharts beanspruchen, wobei Anti-Hero ihr neunter Nummer-eins-Hit wurde. Damit gelang es ihr zum vierten Mal, mit einem Album und einem Lied gleichzeitig auf Platz eins einzusteigen. Außerdem war es ihr erstes Nummer-eins-Album in Deutschland.[58]

Im November 2022 kündigte Swift mit der The Eras Tour ihre sechste Konzerttournee an.[59] Bei einem Auftritt in Seattle registrierten Seismographen in der Metropolregion Seattle für Menschen nicht wahrnehmbare Erschütterungen der Erde, die die Fans während des Konzertes verursachten.[60] Nach nur 60 der über 150 Konzerte wurde die Tournee als erste Tournee eingestuft, die über eine Milliarde US-Dollar einnahm.[61] 2023 erreichte sie mit dem Song Cruel Summer aus dem vier Jahre zuvor erschienenen Album Lover zum zehnten Mal die Spitze der amerikanischen Charts. Durch Swifts Darbietung des Liedes auf dem Konzertfilm Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour erhielt es einen Popularitätsschub.[62] Direkt im Anschluss erfolgte mit der neuen Single Is It Over Now?, die als Bonustrack auf der neuaufgenommenen Version von 1989 enthalten ist, ihr elfter Nummer-eins-Hit in den USA.

Bei den Grammy Awards 2024 gewann Swift in den Kategorien „Album of the Year“ und „Best Pop Vocal Album“ für Midnights. Somit hält sie mehr „Album of the Year“-Awards als jeder andere Künstler. In ihrer Dankesrede kündigte Swift ihr elftes Studioalbum The Tortured Poets Department für den 19. April 2024 an.[63]

Markenrechte

Swift hat sich bei ihrem Album 1989 nicht nur die Rechte an den Titeln und an der Musik schützen lassen, sondern auch an einzelnen Textzeilen wie „This sick beat“, „Party like it’s 1989“ oder „Nice to meet you. Where you been?“.[64][65] Die Band Peculate kritisierte dies als direkten „Angriff auf die freie Rede“ und nahm einen Song mit dem Titel This Sick Beat auf, dessen Text „auch einzig und allein aus der von Taylor Swift geschützten Phrase besteht“.[65]

Im Juli 2019 kaufte Scooter Braun das Musiklabel Big Machine Records, das die ersten sechs Alben von Taylor Swift besitzt. The Wall Street Journal schätzte den Verkaufspreis auf 300 Millionen US-Dollar. Swift möchte die Rechte an ihrer Musik selbst erwerben und bereue es, mit 15 den Vertrag mit Big Machine Records unterschrieben zu haben.[66] Unter anderem wegen Scooters enger Zusammenarbeit mit Kanye West bezeichnete Swift ihn als „Tyrann“ und diese Situation als ihren „schlimmsten Albtraum“. 2016 hatte West in seinem Lied Famous darauf angespielt, für Swifts Erfolg verantwortlich zu sein, indem er sang: „Ich habe das Gefühl, dass Taylor und ich immer noch Sex haben könnten. Warum? Ich habe diese Schlampe berühmt gemacht“ (original “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex. Why? I made that bitch famous”). Diese und weitere Kontroversen führten zu einer öffentlichen Hetze gegen Swift, welche ein einjähriges Verschwinden von Swift und ihr siebtes Studioalbum Reputation zufolge hatte.[67] Da Big Machine Records nur die Rechte an den Master Recordings, aber nicht die an den Songs selbst hält, spielt Swift seit 2021 ihre vergangenen Alben neu ein, versehen mit dem Namenszusatz „Taylor’s Version“.[68] Im April 2021 verkaufte Braun seine Ithaca Holding für fast 1 Milliarde US-Dollar an die Big Hit America Inc., eine Tochter der Hybe Corporation.[69]

Taylor’s Version

Taylor’s Version, auch bekannt als Taylor Swift’s Re-Recordings, bezieht sich auf eine Reihe von Musikalben, die von der amerikanischen Singer-Songwriterin Taylor Swift neu aufgenommen wurden. Die Notwendigkeit für diese Neuauflagen entstand aus einem langwierigen Lizenzstreit zwischen Swift und ihrem ehemaligen Plattenlabel, Big Machine Label Group, der im Jahr 2019 öffentlich wurde. Swift behauptete, dass Big Machine die Rechte an ihren ersten sechs Studioalben besitze und sich weigere, ihr diese Rechte zu übertragen.

Um die Kontrolle über ihre Musik zurückzugewinnen und das Eigentum an ihren eigenen Songs zu sichern, kündigte Swift im August 2019 an, dass sie plane, ihre Alben neu aufzunehmen. Sie begann mit dieser Aufgabe im November 2020 und veröffentlichte seitdem mehrere ihrer Alben erneut. Diese Neuauflagen werden oft als „Taylor’s Version“ bezeichnet, um sie von den Originalaufnahmen zu unterscheiden, die immer noch unter der Kontrolle von Big Machine stehen.

Die Neuauflagen sind bemerkenswert, da sie Swift die Möglichkeit geben, die Alben mit reiferer Stimme und verbesserter künstlerischer Kontrolle neu aufzunehmen. Die Fans unterstützen Taylor’s Version als Zeichen der Solidarität mit Swift und als Protest gegen die Praktiken der Musikindustrie, insbesondere hinsichtlich des Eigentums und der Kontrolle über kreative Werke.

Die ersten Neuauflagen wurden mit Spannung erwartet, insbesondere ihr zweites Studioalbum „Fearless“, das im April 2021 als „Fearless (Taylor’s Version)“ veröffentlicht wurde. Die Neuauflagen von Swifts früheren Alben haben sowohl kommerziell als auch kritisch großen Erfolg erzielt und wurden von Fans und Kritikern gleichermaßen positiv aufgenommen.

Infolge von Taylor’s Version hat Swift ihre Position als eine der einflussreichsten und künstlerisch mächtigsten Persönlichkeiten in der Musikindustrie weiter gestärkt. Ihre Entscheidung, ihre Alben neu aufzunehmen, hat wichtige Diskussionen über das Urheberrecht, die Unabhängigkeit von Künstlern und die Bedeutung der künstlerischen Kontrolle in der Musikindustrie angestoßen.

Politische Position

Vom Rechtspopulisten Milo Yiannopoulos und anderen Vertretern der Alt-Rights wurde Swift als Ikone verehrt. Andre Anglin, Autor des neonazistischen Blogs The Daily Stormer, bezeichnete die Sängerin als „reine arische Göttin“. Swift bezog dazu nicht direkt Stellung, sondern versuchte, die Beiträge löschen zu lassen. Daher wurde ihr damals vorgeworfen, sich nicht von Neonazis zu distanzieren.[70][71][72] In einem späteren Interview mit Rolling Stone erklärte Swift “There’s literally nothing worse than white supremacy. It’s repulsive. There should be no place for it” („Es gibt buchstäblich nichts Schlimmeres als weiße Vorherrschaft. Sie ist abscheulich. Dafür sollte es keinen Platz geben“).[73]

In einem Interview mit der Zeitschrift Time begründete Swift (damals 22-jährig) ihre Zurückhaltung in Sachen Politik damit, dass sie andere Menschen nicht beeinflussen wolle, solange sie noch nicht genug wisse, um den Leuten zu sagen, wen sie wählen sollen.[74] Zudem fürchtete Swift, durch politisches Engagement in ähnliche Situationen wie die US-amerikanische Country-Band The Chicks im Frühjahr 2003 zu gelangen, als sich ein Band-Mitglied darüber äußerte, beschämt zu sein, weil der Präsident der Vereinigten Staaten (damals George W. Bush) ebenfalls aus Texas komme.[75] Daraufhin erhielt die Band scharfe Kritik und wurde von zahlreichen Menschen der US-amerikanischen Bevölkerung boykottiert.

Im Oktober 2018 gab Swift ihre Unterstützung für die Kandidaten der demokratischen Partei bei der Kongresswahl bekannt.[76] Im Mai 2020 warf Swift Donald Trump vor, den Todesfall George Floyd durch seinen Rassismus mitverschuldet zu haben und die daraus entstandenen Konflikte zu befeuern.[77] In der US-Wahl 2008 warb Swift für die Every-Woman-Counts-Kampagne, welche das politische Engagement von Frauen stärken sollte.[78] Zudem unterstützte sie die Time’s-Up-Bewegung gegen sexuellen Missbrauch. Doch auch in ihren Liedern verbreitet Swift feministische Werte: Mit ihrem Lied The Man kritisiert sie die Rollenbilder der jeweiligen Geschlechter, indem sie darüber singt, wie es wäre, ein Mann zu sein.

„I’d be a fearless leader, I’d be an alpha type, When everyone believes ya, What’s that like?“

„Ich wäre ein furchtloser Anführer,

Ich wäre der Alpha-Typ,

Wenn dir alle glauben,

Wie ist das?“

In champagne problems aus dem Album evermore bestärkt sie ihre Kritik, unter anderem mit den Versen “‘She would’ve made such a lovely bride, what a shame she’s fucked in her head’, they said” („Man sagte: ‚Sie wäre so eine schöne Braut gewesen. Eine Schande, dass sie nicht ganz richtig im Kopf ist‘“). Dabei geht sie auf die schlechte Nachrede anderer ein, nachdem die Protagonistin des Liedes – wider traditionelle Erwartungen – eine Ehe ablehnt.[79] the last great american dynasty handelt erneut über eine weibliche Protagonistin (genauer Rebekah Harkness), welche zu Unrecht dafür negativ verurteilt worden sein soll, Freude zu haben und sich gegen gesellschaftliche Erwartungen (von ihr als Frau) zu verhalten. Nach der Veröffentlichung des Liedes All Too Well (10 Minute Version) (Taylor’s Version) [From The Vault], verkaufte Taylor Swift Schlüsselanhänger mit der Aufschrift F*ck The Patriarchy („Fick das Patriarchat“), einem Ausruf aus der zweiten Strophe des Liedes.[80] In einem Interview im britischen Magazin The Guardian bekannte Swift sich Pro-Choice.[81]

Mit You Need to Calm Down spricht sich Swift deutlich für die LGBTQIA+-Community aus. In der zweiten Strophe weist sie durch „Why are you mad when you could be GLAAD?“ („Weshalb bist du sauer, wenn du fröhlich sein könntest?“) auf die US-amerikanische Non-Profit-Organisation GLAAD hin, an welche sie zuvor einen Geldbetrag spendete.[82] GLAAD setzt sich öffentlich gegen Diskriminierung aufgrund von Geschlechtsidentität und sexueller Orientierung ein. Zudem spendete sie am 8. April 2019 113.000 US-Dollar an das pro-LGBTQIA+ Tennessee Equality Project.[83]

Während der Black-Lives-Matter-Bewegung spendete Swift Geld an die Organisation NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. welche sich für afroamerikanische Menschen einsetzt.[84]

Bei der US-Präsidentschaftswahl 2020 unterstützte sie Joe Biden.[85]

Laut einer Umfrage des Instituts Redfield & Wilton Strategies im Vorfeld der US-Präsidentschaftswahl 2024 gaben 18 Prozent der befragten Wahlberechtigten an, eher für einen von Swift bevorzugten Kandidaten stimmen zu wollen.[86]

Rezeption und popkultureller Einfluss

Swift hat von Beginn ihrer Karriere an für ihr musikalisches Tun meist positive Kritiken erhalten.[87] So attestierte die New York Times ihr bereits im Jahr 2008 gute Liedermacherqualitäten bei fehlender Naivität.[88] Sie hat unter anderem zahlreiche Mainstream- und Indie-Musikkünstler beeinflusst.[89] Das Billboard-Magazine stellte fest, dass nur wenige Künstler wie Swift Charterfolg, Kritikerlob und Fanunterstützung haben und dass dies ihr ermögliche, eine weitreichende Wirkung zu erzielen.[90] So erstreckt sich ihr Charterfolg auch auf Asien und Großbritannien, wo Country-Musik zuvor nicht sehr populär war.[91][92] Sie war eine der ersten Country-Musiker, die Online-Marketing-Techniken wie MySpace einsetzte, um für ihre Arbeit zu werben.[93][94]

Laut Entertainment Weekly hat der kommerzielle Erfolg ihres gleichnamigen Debütalbums der jungen Plattenfirma Big Machine geholfen, Garth Brooks und Jewel unter Vertrag zu nehmen.[94] Nach Swifts Aufstieg interessierten sich Country-Labels wieder mehr dafür, Musiker unter Vertrag zu nehmen, die ihre eigene Musik schreiben.[95] Laut Kritikern habe Swift eine Musik entwickelt, die Wiedererkennungswert habe und selbst in Alben von Country-Sängerinnen, die von ihr inspiriert wurden, herauszuhören sei. Dies soll etwa bei Kacey Musgraves, Maren Morris und Kelsea Ballerini hörbar sein. Die Zeitschrift Rolling Stone führte Swifts Country-Musik als einen der größten Einflüsse auf die Popmusik der 2010er Jahre auf und platzierte sie auf Platz 80 in ihrer Liste der 100 größten Country-Künstler aller Zeiten.[96] Ihre Bühnenauftritte trugen zum „Taylor-Swift-Faktor“ bei, einem Phänomen, dem der Anstieg der Gitarrenverkäufe an Frauen, eine zuvor nahezu ignorierte Bevölkerungsgruppe, zugeschrieben wird.[97][98] Pitchfork Media meint, Swift habe die zeitgenössische Musiklandschaft mit ihrem „beispiellosen Weg vom jugendlichen Country-Wunderkind zur globalen Pop-Sensation“ und einer „einzigartig scharfsinnigen“ Diskographie, die konsequent sowohl musikalische als auch kulturelle Veränderungen berücksichtigt, verändert.[99] Laut The Guardian führt Swift mit ihrer „ehrgeizigen künstlerischen Vision“ die Wiedergeburt des „Poptimismus“ im 21. Jahrhundert an.[100]

Swifts millionenfach verkaufte Alben werden nach dem Ende der Album-Ära in den 2010er Jahren von Publikationen als Anomalie in der von Streaming dominierten Musikbranche angesehen.[101][102] Swift ist die einzige Künstlerin, von der sich vier Alben in einer Woche über eine Million Mal verkauft haben, seit Nielsen SoundScan 1991 mit der Verfolgung der Verkäufe begonnen hat.[101] The Atlantic stellt fest, dass Swifts „Herrschaft“ der Konvention widerspricht, dass die erfolgreiche Phase der Karriere eines Künstlers selten länger als ein paar Jahre dauert.[103] Swift gilt als Verfechterin von privat geführten Plattenläden und trug zu einem Vinyl-Revival im 21. Jahrhundert bei.[104][105] Variety nannte Swift die „Queen of Stream“, als sie auch auf Musik-Streaming-Plattformen mehrere Rekorde aufstellte.[106] Auf Spotify war sie die erste Künstlerin, die 100 Millionen monatliche Zuhörer erreichte.[107]

Laut Billboard,[108] Business Insider[109] und The New York Times haben ihre Alben eine Generation von Sängern und Songschreibern inspiriert.[110] Im Juni 2015 veranlasste Swift die Firma Apple, die Bezahlung von Künstlern zu überdenken und großzügiger zu gestalten. Apple hatte geplant, im Rahmen seines neuen Streamingdienstes Apple Music den Nutzern drei kostenlose Probemonate zu gewähren, wobei die Künstler leer ausgehen sollten. Indem sie sich weigerte, Apple ihr Album 1989 zur Verfügung zu stellen, bewirkte Swift ein Umdenken. Apple wird zwar die Titel weiterhin kostenfrei anbieten, die Künstler nun jedoch finanziell entschädigen.[111]

Journalisten erklärten, dass sie Debatten über Reformen des Musikstreamings gefördert und das Bewusstsein für geistige Eigentumsrechte bei jüngeren Musikern geweckt habe.[112][113][114] Verschiedene Quellen halten Swifts Musik aufgrund ihres Erfolgs, ihrer Vielseitigkeit, ihrer Internetpräsenz und ihrer Shows für repräsentativ und paradigmatisch für die Millennials.[115][116][117][118] „In Anerkennung ihres immensen Einflusses auf die Musik auf der ganzen Welt“ erhielt Swift den Global Icon Award.[119]

Swift ist Gegenstand akademischer Studien;[120] die University of Texas at Austin,[121] New York University[122] und Queen’s University im kanadischen Kingston bieten Kurse über Swifts Diskographie in literarischen und gesellschaftspolitischen Kontexten an.[123] Der Naturschutzwissenschaftler Jeff Opperman hob einen Bericht der Association for Psychological Science aus dem Jahr 2017 über den Niedergang naturbezogener Wörter in der Populärkultur hervor und meinte, dass Swifts Lieder „mit der Sprache und den Bildern der natürlichen Welt gefüllt“ seien und die Natur in die zeitgenössische Kultur zurückbringen.[124] Einige ihrer Lieder werden von Evolutionspsychologen untersucht, um die Beziehung zwischen populärer Musik und menschlichen Paarungsstrategien zu verstehen.[125][126]

Mit 274 Millionen Followern gehört der Instagram-Account von Swift zu den Top-15 der Welt.[127] Sie hat laut IFPI mehr als 300 Millionen Tonträger verkauft (Stand: August 2023) und gehört damit zu den weltweit erfolgreichsten Künstlern.[128] Sie löste Barbra Streisand mit zwölf Nummer-eins-Alben als in der Hinsicht führende Künstlerin ab.[129] und brach den von Elvis Presley gehaltenen Rekord, die längste Zeit als Solokünstler die Billboard-Albumcharts anzuführen.[130] Zudem ist sie die erste Person, die gleichzeitig alle zehn Plätze der Top Ten der amerikanischen Singlecharts besetzte.[131] Swift hält mehr als 100 Guinness-Weltrekorde.[132]

Spenden

Swift ist bekannt für ihre philanthropischen Bemühungen.[133] Im Jahr 2015 belegte sie den ersten Platz auf der „Gone Good“-Liste von DoSomething,[134] nachdem sie den „Star of Compassion“ von den Tennessee Disaster Services und den „Big Help Award“ von den Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards für ihr „Engagement anderen zu helfen“ und „inspirierendes Handeln“ erhalten hatte.[135][136] Im Jahr 2008 spendete sie 100.000 US-Dollar an das Rote Kreuz, um den Opfern der Überschwemmung in Iowa zu helfen.[137] 2009 sang sie beim BBC-Konzert Children in Need und sammelte 13.000 Pfund für den guten Zweck.[138] Swift trat bei verschiedenen Wohltätigkeitsveranstaltungen auf, darunter beim Sound Relief-Konzert in Sydney.[139] Als die Reaktion auf die Überschwemmungen in Tennessee im Mai 2010 spendete Swift während eines Spendenmarathons, der von WSMV veranstaltet wurde, 500.000 US-Dollar.[140] Im Jahr 2011 nutzte Swift eine Generalprobe ihrer Speak Now-Tour als Benefizkonzert für die Opfer der jüngsten Tornados in den USA und sammelte mehr als 750.000 US-Dollar.[141] 2016 spendete sie 1 Million US-Dollar für die Fluthilfemaßnahmen in Louisiana und 100.000 US-Dollar an den Dolly Parton Fire Fund.[142][143] Swift unterstützte Lebensmittelbanken nach dem Hurrikan Harvey in Houston im Jahr 2017 und bei jedem Stopp der Eras Tour im Jahr 2023.[144][145] Außerdem beschäftigte sie während der gesamten Tour direkt lokale Unternehmen und zahlte Bonuszahlungen in Höhe von 55 Millionen US-Dollar an ihre gesamte Crew.[146][147] In den Jahren 2020 und 2023 spendete Swift jeweils 1 Million US-Dollar für die Tornadohilfe in Tennessee.[148][149]

Vermögen

Swift verfügt Stand 2023 über Immobilien in New York, Nashville, Los Angeles (Samuel Goldwyn Estate) und Westerly. Ihr Nettovermögen wurde im selben Jahr von Forbes auf 740 Millionen US-Dollar[150][151] und von Bloomberg auf 1,1 Milliarden Dollar beziffert.[152]

Auszeichnungen

Zu Swifts Auszeichnungen zählen 14 Grammy Awards, darunter vier für das Album des Jahres[2], 40 American Music Awards (was keinem anderen Interpreten gelang[153]), 29 Billboard Music Awards (die meisten für eine Sängerin), 23 MTV Video Music Awards und ein Emmy Award. Sie ist in Rankings wie Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time,[154] Billboard’s Greatest of All Time Artists, The Time 100 und Forbes Celebrity 100 vertreten. Sie hat seit 2007 mehr als 50 Auszeichnungen insbesondere im Country-Bereich erhalten. Dazu zählen unter anderem die Country Music Association Awards, die CMT Music Awards und die Academy of Country Music Awards, bei denen sie mehrfach ausgezeichnet wurde.

Weitere Auszeichnungen erhielt sie bei den BMI Awards, den American Music Awards, den Teen Choice Awards, den People’s Choice Awards, den Emmy Awards und den Billboard Music Awards. 2015 gewann sie insgesamt acht der 40 zu vergebenden Billboard Awards.[155] Bei den People’s Choice Awards gewann ihr Song Only the Young (von der Dokumentation Miss Americana) in der Kategorie The Soundtrack Song of 2020.[156] Von MTV wurde sie 23 mal mit dem Video Music Award und zwölfmal mit dem Europe Music Awards ausgezeichnet.[157][158]

- 2009: in der Kategorie Artist of the Year (Female)

- 2011: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Artist

- 2011: in der Kategorie Top Country Artist

- 2011: in der Kategorie Top Country Album für Speak Now

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Artist

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Female Artist

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Artist

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Country Artist

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Digital Songs Artist

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Album für Red

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Country Album für Red

- 2013: in der Kategorie Top Country Song für We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Artist

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Female Artist

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Artist

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Hot 100 Artist

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Digital Songs Artist

- 2015: in der Kategorie Billboard Chart Achievement Award (Fan Voted)

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Billboard Album für 1989

- 2015: in der Kategorie Top Streaming Song (Video) für Shake It Off

- 2016: in der Kategorie Top Touring Artist

- 2018: in der Kategorie Top Female Artist

- 2018: in der Kategorie Top Selling Album für Reputation

- 2021: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Artist

- 2021: in der Kategorie Top Female Artist

- 2022: in der Kategorie Top Billboard 200 Artist

- 2022: in der Kategorie Top Country Artist

- 2022: in der Kategorie Top Country Female Artist

- 2022: in der Kategorie Top Country Album für Red (Taylor’s Version)

- 2010: in der Kategorie Best Female Country Vocal Performance für White Horse

- 2010: in der Kategorie Best Country Song für White Horse

- 2010: in der Kategorie Best Country Album für Fearless

- 2010: in der Kategorie Album of the Year für Fearless

- 2012: in der Kategorie Best Country Solo Performance für Mean

- 2012: in der Kategorie Best Country Song für Mean

- 2013: in der Kategorie Best Song Written for Visual Media für Safe & Sound

- 2016: in der Kategorie Album of the Year für 1989

- 2016: in der Kategorie Best Pop Vocal Album für 1989

- 2016: in der Kategorie Best Music Video für Bad Blood (feat. Kendrick Lamar)

- 2021: in der Kategorie Album of the Year für folklore

- 2023: in der Kategorie Best Music Video für All Too Well: The Short Film

- 2024: in der Kategorie Album of the Year für Midnights

- 2024: in der Kategorie Best Pop Vocal Album für Midnights

- 2009: in der Kategorie Best Female Video für You Belong with Me

- 2013: in der Kategorie Best Female Video für I Knew You Were Trouble

- 2015: in der Kategorie Video of the Year für Bad Blood (feat. Kendrick Lamar)

- 2015: in der Kategorie Best Female Video für Blank Space

- 2015: in der Kategorie Best Pop Video für Blank Space

- 2015: in der Kategorie Best Collaboration für Bad Blood (feat. Kendrick Lamar)

- 2017: in der Kategorie Best Collaboration für I Don't Wanna Live Forever (feat. Zayn)

- 2019: in der Kategorie Video of the Year für You Need to Calm Down

- 2019: in der Kategorie Video for Good für You Need to Calm Down

- 2019: in der Kategorie Best Visual Effects für Me! (feat. Brendon Urie)

- 2020: in der Kategorie Best Direction für The Man

- 2022: in der Kategorie Video of the Year für All Too Well: The Short Film

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Longform Video für All Too Well: The Short Film

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Direction für All Too Well: The Short Film

- 2023: in der Kategorie Video of the Year für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Song of the Year für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Best Pop für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Best Direction für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Best Cinematography für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Best Visual Effects für Anti-Hero

- 2023: in der Kategorie Artist of the Year

- 2023: in der Kategorie Show of the Summer

- 2023: in der Kategorie Album of the Year für Midnights

- 2012: in der Kategorie Best Live Act für die Speak Now World Tour

- 2012: in der Kategorie Best Female

- 2012: in der Kategorie Best Look

- 2015: in der Kategorie Best Song für Bad Blood (feat. Kendrick Lamar)

- 2015: in der Kategorie Best US Act

- 2019: in der Kategorie Best Video für ME! (feat. Brendon Urie)

- 2019: in der Kategorie Best US Act

- 2021: in der Kategorie Best US Act

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Artist

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Pop

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Video für All Too Well: The Short Film

- 2022: in der Kategorie Best Longform Video für All Too Well: The Short Film

Bei den Billboard Women in Music wurde Swift unter anderem 2019 als Women of the Decade gekürt.[159] Im April 2022 wurde mit Nannaria swiftae ein Tausendfüßler nach ihr benannt.[160] Im Rahmen der The Eras Tour wurde Swift in Arlington, Tampa und Atlanta der Schlüssel zur Stadt überreicht. In zahlreichen Städten wurden Orts- und Straßennamen Swift zu Ehren ihren Aufenthalt lang umbenannt und Swift-bezogene Feiertage eingeführt. Tampa und Santa Clara ernannten Swift zur Ehrenbürgermeisterin.[161] Im Jahr 2023 wurde sie von der Zeitschrift Time zur Person des Jahres ernannt;[162] erstmals ehrte die Time damit eine Person wegen ihres künstlerischen Schaffens als Person des Jahres.[163] Im selben Jahr kürte Spotify Swift zum meistgestreamten Künstler[164] und Google sie zum meistgesuchten Singer-Songwriter jenes Jahres.[165]

Kontroversen

Kanye West

Bei den MTV Video Music Awards 2009, bei denen Swift für das beste Musikvideo ausgezeichnet wurde, störte Rapper Kanye West die Dankesrede von Taylor Swift. Er nahm ihr das Mikrofon weg und verwies auf das Video von Beyoncé, welches er für besser hielt. Als Taylor Swift bei den MTV Video Music Awards 2015 West den Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award überreichte, scherzte dieser, dass MTV Swift für eine höhere Einschaltquote eingeladen habe.[166] 2016 geriet West nach der Veröffentlichung seines Liedes Famous erneut unter Kritik. In einem Vers singt der Rapper: „Ich habe das Gefühl, dass Taylor und ich immer noch Sex haben könnten. Warum? Ich habe diese Schlampe berühmt gemacht“ (original „I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex. Why? I made that bitch famous“). Wests Partnerin Kim Kardashian veröffentlichte daraufhin ein Telefonat, in welchem Swift der Verwendung des Verses zugestimmt haben soll. 2020 erwies sich die Aufnahme jedoch als bearbeitet.[167]

Flugverhalten

Zwischen Januar und Juli 2022 unternahm Swift etwa 170 Flüge mit ihrem Privatjet. Dabei soll das Flugzeug fast 8300 Tonnen Kohlendioxid ausgestoßen haben.[168] Das sind 1.184 Mal mehr als die jährlichen Emissionen einer Durchschnittsperson. Die Flüge ihres Privatjets beliefen sich durchschnittlich auf 80 Minuten und rund 224 Kilometer. Der kürzeste Flug dauerte 36 Minuten, von Missouri nach Nashville. Unter Prominenten hatte Swift damit in jenem Jahr die meisten Meilen zurückgelegt und damit den größten CO2-Fußabdruck hinterlassen. Für ihr umweltschädliches Verhalten wurde Swift kritisiert.[169] Ein Student, der Privatjets von Prominenten verfolgt, behauptete, Taylor Swifts Anwälte hätten damit gedroht, ihn zu verklagen, falls er nicht aufhöre, ihre Flugrouten im Internet preiszugeben.[170] Anfang 2024 nutzte sie erneut ihr Flugzeug, um innerhalb St. Louis eine Strecke von 28 Meilen zurückzulegen. Die Zeitersparnis bei diesem 13-minütigen Flug waren 17 Minuten.[171] Um nach einem Auftritt in Tokio im Februar 2024 den Superbowl in Las Vegas besuchen zu können, nutzte sie erneut ihren Privatjet und emittierte rund 7.000 Kilogramm Kohlendioxid, eine Menge, für die ein durchschnittlicher deutscher Verbraucher mehr als sieben Monate benötigt, wie die Frankfurter Rundschau bemerkte.[172]

Plagiatsvorwürfe

Sean Hall und Nathan Butler von der Band 3WL behaupteten, dass Swifts Song Shake It Off von 2014 ein Plagiat ihres Songs Playas Gon’ Play sei. Der Text „players gonna play, play, play, play“ und „the haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate“ verletze das Urheberrecht ihres Songs aus dem Jahr 2000, der die Zeilen „Playas, they gonna play / And haters, they gonna hate“ enthalte. Andererseits versicherte Swift, sie hätte bis zur Klageeinreichung 2017 weder den Song Playas Gon’ Play noch die Band 3LW gekannt. Im Jahr 2022 wurde die Klage nach fünf Jahren Gerichtsverhandlungen von den Klägern zurückgezogen.[173][174]

Filmografie

- 2009: Jonas Brothers – The 3D Concert

- 2009: CSI: Vegas (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Fernsehserie, Episode 9x16)

- 2009: Hannah Montana – Der Film (Hannah Montana: The Movie)

- 2010: Valentinstag (Valentine’s Day)

- 2012: Der Lorax (The Lorax, Sprechrolle)

- 2013: New Girl (Fernsehserie, Episode 2x25 Elaine’s Big Day)

- 2014: Hüter der Erinnerung – The Giver (The Giver)

- 2015: The 1989 World Tour Live

- 2018: Taylor Swift: Reputation Stadium Tour

- 2019: Cats

- 2020: Miss Americana

- 2020: City of Lover

- 2020: Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions (auch Regie, Produktion, Drehbuch und Musik)

- 2021: All Too Well: The Short Film (insbesondere Drehbuch, Regie und Musik)

- 2022: Amsterdam

- 2023: Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour

Diskografie

Studioalben

| Jahr | Titel Musiklabel | Höchstplatzierung, Gesamtwochen, AuszeichnungChartplatzierungenChartplatzierungen (Jahr, Titel, Musiklabel, Platzierungen, Wochen, Auszeichnungen, Anmerkungen) | Anmerkungen | [↑]: gemeinsam behandelt mit vorhergehendem Eintrag; [←]: in beiden Charts platziert | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Taylor Swift Big Machine Records (UMG) | — | — | — | UK81 (3 Wo.)UK | US5 ×7 (284 Wo.)US | Country1 (235 Wo.)Country |

Erstveröffentlichung: 24. Oktober 2006 Verkäufe: + 7.750.000[175] | |

| 2008 | Fearless Big Machine Records (UMG) | DE2a (26 Wo.)DE | AT2a (19 Wo.)AT | CH3a (13 Wo.)CH | UK5 ×2 (64 Wo.)UK | US1 (261 Wo.)US | Country1 (345 Wo.)Country |

Erstveröffentlichung: 11. November 2008 Verkäufe: + 12.249.500 | |

| Fearless (Taylor’s Version) Republic Records (UMG)[DE: ↑][AT: ↑][CH: ↑] | UK1 (35 Wo.)UK | US1 (… Wo.)US | Country1 (… Wo.)Country |

Neueinspielung: 9. April 2021 Verkäufe: + 1.299.000 | |||||

| 2010 | Speak Now Big Machine Records (UMG) | DE2b (20 Wo.)DE | AT1b (19 Wo.)AT | CH1b (28 Wo.)CH | UK6 (15 Wo.)UK | US1 ×6 (193 Wo.)US | Country1 (… Wo.)Country |

Erstveröffentlichung: 25. Oktober 2010 Verkäufe: + 7.181.500 | |

| Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) Republic Records (UMG) | DE35 (19 Wo.)DE | AT26 (18 Wo.)AT[CH: ↑] | UK1 (… Wo.)UK | US1 (… Wo.)US | Country1 (… Wo.)Country |

Neueinspielung: 7. Juli 2023 Verkäufe: + 172.500 | |||

| 2012 | Red Big Machine Records (UMG) | DE5 (70 Wo.)DE | AT3 (52 Wo.)AT | CH7c (32 Wo.)CH | UK1 ×2 (85 Wo.)UK | US1 ×7 (185 Wo.)US | Country1 (328 Wo.)Country |

Erstveröffentlichung: 22. Oktober 2012 Verkäufe: + 9.318.000 | |

| Red (Taylor’s Version) Republic Records (UMG) | DE60 (15 Wo.)DE | AT47 (14 Wo.)AT[CH: ↑] | UK1 (… Wo.)UK | US1 (… Wo.)US | Country1 (… Wo.)Country |

Neueinspielung: 12. November 2021 Verkäufe: + 2.075.000 | |||

| 2014 | 1989 Big Machine Records (UMG) | DE4 (131 Wo.)DE | AT4 ×3 (135 Wo.)AT | CH1d (… Wo.)CH | UK1 ×5 (… Wo.)UK | US1 ×9 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 27. Oktober 2014 Verkäufe: + 13.438.000 | |

| 1989 (Taylor’s Version) Republic Records (UMG) | DE1 (… Wo.)DE | AT1 (… Wo.)AT[CH: ↑] | UK1 (… Wo.)UK | US1 (… Wo.)US | — |

Neueinspielung: 27. Oktober 2023 Verkäufe: + 595.000 | |||

| 2017 | Reputation Big Machine Records (UMG) | DE2 (… Wo.)DE | AT1 (… Wo.)AT | CH1 (… Wo.)CH | UK1 ×2 (… Wo.)UK | US1 ×3 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 10. November 2017 Verkäufe: + 4.690.000 | |

| 2019 | Lover Republic Records (UMG) | DE2 (… Wo.)DE | AT2 (… Wo.)AT | CH2 (… Wo.)CH | UK1 ×2 (… Wo.)UK | US1 ×3 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 23. August 2019 Verkäufe: + 4.755.000 | |

| 2020 | Folklore Republic Records (UMG) | DE5 (… Wo.)DE | AT2 (… Wo.)AT | CH1 (56 Wo.)CH | UK1 ×2 (… Wo.)UK | US1 ×2 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 24. Juli 2020 Verkäufe: + 3.097.500 | |

| Evermore Republic Records (UMG) | DE5 (59 Wo.)DE | AT2 (31 Wo.)AT | CH4 (16 Wo.)CH | UK1 (… Wo.)UK | US1 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 11. Dezember 2020 Verkäufe: + 1.614.500 | ||

| 2022 | Midnights Republic Records (UMG) | DE1 (… Wo.)DE | AT1 (… Wo.)AT | CH1 (… Wo.)CH | UK1 ×2 (… Wo.)UK | US1 ×2 (… Wo.)US | — |

Erstveröffentlichung: 21. Oktober 2022 Verkäufe: + 3.526.000 | |

Tourneen

| Jahr | Name | Anzahl an Konzerten |

|---|---|---|

| 2009–2010 | Fearless Tour | 111 |

| 2011–2012 | Speak Now World Tour | 110 |

| 2013–2014 | The Red Tour | 86 |

| 2015 | The 1989 World Tour | 85 |

| 2018 | Reputation Stadium Tour | 53 |

| 2023–2024 | The Eras Tour | 151 |

Im September 2019 wurde außerdem eine Welttournee bezüglich Swifts siebtem Studioalbum Lover für den Sommer 2020 angekündigt.[176] Mit der Ausbreitung der COVID-19-Pandemie wurde das sogenannte Lover Fest im Februar 2020 abgesagt.[177]

Literatur

- Chloe Govan: Taylor Swift: Her Story. Omnibus Press, London 2012, ISBN 978-1-78038-354-5.

- Louisa Jepson: Taylor Swift. Simon & Schuster, New York 2013, ISBN 978-1-4711-3087-8.

- Chas Newkey-Burden: Taylor Swift: The Whole Story. HarperCollins UK, London 2014, ISBN 978-0-00-754421-9.

- Liv Spencer. Taylor Swift: The Platinum Edition. 2. Auflage. ECW Press, Toronto 2013, ISBN 978-1-77090-405-7.

Weblinks

- Offizielle Website von Taylor Swift

- Taylor Swift bei Discogs

- Taylor Swift bei laut.de

- Taylor Swift bei IMDb

- Taylor Swift bei AllMusic (englisch)

- Taylor Swift bei Universal Music Deutschland

- Literatur von und über Taylor Swift im Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Taylor Swift named IFPI Global Recording Artist of 2014. International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, 23. Februar 2015, abgerufen am 28. September 2015 (englisch).

- ↑ a b Taylor Swift made history by winning a Grammy for Album Of The Year for a 4th time. 5. Februar 2024, abgerufen am 5. Februar 2024 (englisch).

- ↑ American Music Awards: Taylor Swift gewinnt sechs Auszeichnungen. In: Der Spiegel. 21. November 2022, ISSN 2195-1349 (spiegel.de [abgerufen am 27. November 2022]).

- ↑ Kimberley Cutter: Taylor Swift's Rise to America's Sweetheart. In: Marie Claire. 2. Juni 2010, abgerufen am 7. Februar 2014.

- ↑ Walter Scott: What Famous Pop Star Is Named After James Taylor? 11. Juni 2015, abgerufen am 31. März 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Erica Cohen: Taylor Swift's father is a Blue Hen. In: UDaily. 23. September 2009, abgerufen am 7. Februar 2014.

- ↑ Lizzie Widdicombe: "You Belong With Me". In: The New Yorker. 10. Oktober 2011, abgerufen am 11. Oktober 2011.

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Biography. In: TV Guide. Abgerufen am 16. Oktober 2011.

- ↑ Taylor Swift song ‘Marjorie’ is a tribute to her late grandmother. 11. Dezember 2020, abgerufen am 31. März 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Growing into superstardom. 1. April 2012, abgerufen am 31. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Returns to Reading Pennsylvania as Maid of Honor in Friend’s Wedding | NBC 10 Philadelphia. 16. September 2016, abgerufen am 31. März 2022.

- ↑ Biography com Editors: Taylor Swift. Abgerufen am 10. September 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Bobby Bones Show: Taylor Swift Interview Part 2. In: Bobby Bones Show (Radio Show). 11. Oktober 2013, abgerufen am 22. Juli 2022.

- ↑ EXCLUSIVE: The real story behind Taylor Swift’s guitar 'legend': Meet the computer repairman who taught the pop superstar how to play. Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift | Biography, Albums, Songs, & Facts | Britannica. Abgerufen am 10. September 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift noch immer in Taylor Lautner verliebt?! In: starflash.de. 15. Oktober 2010, abgerufen am 6. Mai 2017.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Wrote Calvin Harris and Rihanna’s ‘This Is What You Came For’. Abgerufen am 14. November 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Trennung nach sechs Jahren Beziehung. In: t-online, 9. April 2023, abgerufen am 15. Juli 2023.

- ↑ Biography com Editors: Taylor Swift. Abgerufen am 10. September 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Condé Nast: Dr. Taylor Swift: Die Sängerin bekam jetzt diesen Doktortitel verliehen und hält gleichzeitig eine Therapiestunde. 19. Mai 2022, abgerufen am 6. September 2022.

- ↑ Rania Aniftos: A Timeline of Taylor Swift & Travis Kelce’s Relationship. In: Billboard.com. 23. Oktober 2023, abgerufen am 26. Oktober 2023 (englisch).

- ↑ Artist Chart History: Taylor Swift – Tim McGraw. In: Billboard. Abgerufen am 24. Januar 2010.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Continues Billboard 200 Dominance. In: Billboard. Abgerufen am 30. Januar 2010.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Edges Susan Boyle For 2009's Top-Selling Album. In: Billboard. Abgerufen am 30. Januar 2010.

- ↑ Week Ending Feb. 8, 2009: Shady's Back (Tell A Friend). In: Yahoo Music Blog (von Paul Grein). 11. Februar 2009, abgerufen am 14. Februar 2010.

- ↑ 36th People's Choice Awards – Favorite Female Artist. In: CBS. Abgerufen am 31. Januar 2010.

- ↑ Fearless Tour 2010. In: Ticketk.com. Abgerufen am 31. Januar 2010.

- ↑ Monica Herrera: Taylor Swift Announces New Album 'Speak Now,' Out Oct. 25. Billboard, 20. Juli 2010, abgerufen am 22. Juli 2010.

- ↑ Chuck Dauphin: Taylor Swift Announces 'Red' Album, New Single. Billboard.com, 13. August 2012, abgerufen am 16. August 2012.

- ↑ RIAA – Gold & Platinum – Searchable Database. Abgerufen am 16. Mai 2015.

- ↑ Billboard. Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Taylorguitars.com. Taylorguitars.com, abgerufen am 7. Februar 2010.

- ↑ 1989 bei TaylorSwift.com. taylorswift.com, abgerufen am 16. Januar 2015.

- ↑ Shake It Off bei Universal-Music.de. universal-music.de, abgerufen am 18. Januar 2015.

- ↑ Joe Lynch: Taylor Swift Reveals New Album 'Reputation' Coming In Nov., First Single Out Thursday. In: Billboard. 23. August 2016, abgerufen am 7. September 2017.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Shares ‘Reputation’ Tracklist, Confirms Ed Sheeran & Future Collab. In: Billboard. (billboard.com [abgerufen am 10. November 2017]).

- ↑ Taylor Swift’s Reputation Stadium Tour highest grossing in US history. In: The Music Network. 2. Dezember 2018, abgerufen am 8. April 2019.

- ↑ Taylor Swift: „You Need To Calm Down“-Musikvideo mit Mega-Starauflauf. Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022.

- ↑ Daniel Kreps: Taylor Swift Cancels All 2020 Tour Dates Due to Coronavirus. In: Rolling Stone. 17. April 2020, abgerufen am 12. Juni 2020 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Madison Bloom: Listen to Taylor Swift’s City of Lover Film Soundtrack. Abgerufen am 12. Juni 2020 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Denise Petski: YouTube Reschedules Virtual Commencement Ceremony With The Obamas, Beyoncé Due To George Floyd Memorial Service – Watch. In: Deadline. 7. Juni 2020, abgerufen am 12. Juni 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ Denise Petski: YouTube Reschedules Virtual Commencement Ceremony With The Obamas, Beyoncé Due To George Floyd Memorial Service – Watch. In: Deadline. 7. Juni 2020, abgerufen am 12. Juni 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ GMA: Taylor Swift announces new album, 'Folklore,' debuts tonight. 23. Juli 2020, abgerufen am 23. Juli 2020 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift bricht den Billboard-Rekord. 4. August 2020, abgerufen am 5. August 2020.

- ↑ Winners & Nominees. Abgerufen am 15. April 2021 (englisch).

- ↑ Destacados TV: Los 10 mejores documentales de cantantes: Billie Eilish, Taylor Swift y más. In: Destacados TV Revista. 13. März 2021, abgerufen am 28. Mai 2021 (mexikanisches Spanisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Neues Album "Evermore" überraschend angekündigt. In: Der Spiegel. 10. Dezember 2020, ISSN 2195-1349 (spiegel.de [abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022]).

- ↑ Andreas Borcholte: Warum Taylor Swift ihr eigenes Album »Fearless« noch mal aufgenommen hat. In: Der Spiegel. 9. April 2021 (spiegel.de [abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022]).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Taylor Swift auf Twitter. In: Twitter. 11. Februar 2021, abgerufen am 9. September 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: Taylor Swift auf Twitter. In: Twitter. 11. Februar 2021, abgerufen am 9. September 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ „Red (Taylor’s Version) [Video Deluxe]“ von Taylor Swift. 12. November 2021, abgerufen am 9. September 2022 (deutsch).

- ↑ Caleb Triscari: Taylor Swift breaks record for longest Number One song with 'All Too Well (10 Minute Version)'. In: NME. 22. November 2021, abgerufen am 9. September 2022 (britisches Englisch).

- ↑ MTV VMAs 2022: Taylor Swift wins and Johnny Depp surprises in chaotic ceremony. 29. August 2022, abgerufen am 6. September 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Gil Kaufman: Taylor Swift Shares Ecstatic Note About ‘Speak Now (Taylor’s Version)’: ‘It’s Here. It’s Yours, It’s Mine, It’s Ours’. In: Billboard. 7. Juli 2023, abgerufen am 15. September 2023 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Chris Willman: Taylor Swift Casts Her Ex, Taylor Lautner, as Co-Star in ‘I Can See You’ Video; the Two Tays Reunite on Stage in Kansas City for Premiere. In: Variety. 8. Juli 2023, abgerufen am 15. September 2023 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift kündigt 1989 als nächstes neu aufgenommenes Album an. In: Musikexpress. 10. August 2023, abgerufen am 16. September 2023 (deutsch).

- ↑ www.bigfm.de: 13 schlaflose Nächte: Taylor Swift mit Album “Midnights”. 30. August 2022, abgerufen am 6. September 2022.

- ↑ www.offiziellecharts.de: TAYLOR SWIFT ERSTMALS AUF PLATZ EINS DER OFFIZIELLEN DEUTSCHEN CHARTS. 28. Oktober 2022, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022.

- ↑ Lisa Respers: Taylor Swift announces ‘The Eras Tour’. In: CNN. 1. November 2022, abgerufen am 5. November 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Konzert in Seattle: Taylor-Swift-Fans lösen ein Erdbeben aus. In: Der Spiegel. 29. Juli 2023, ISSN 2195-1349 (spiegel.de [abgerufen am 29. Juli 2023]).

- ↑ Sanj Atwal: Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour breaks record as highest-grossing music tour ever. In: Guinness World Records. 12. Dezember 2023, abgerufen am 13. Dezember 2023 (englisch).

- ↑ Gary Trust: Taylor Swift’s ‘Cruel Summer’ Hits No. 1 on Billboard Hot 100, Becoming Her 10th Leader. In: Billboard. 23. Oktober 2023, abgerufen am 26. Oktober 2023 (englisch).

- ↑ Katharina James, dpa, AP: Popsängerin: Taylor Swift stellt Grammy-Rekord auf und kündigt neues Album an. In: Die Zeit. 5. Februar 2024, ISSN 0044-2070 (zeit.de [abgerufen am 5. Februar 2024]).

- ↑ Markenrecht für Textzeilen: Patentierte Worthülsen. taz.de, 2. Februar 2015, abgerufen am 6. Februar 2015.

- ↑ a b Kai Leichtlein: Metal-Band wehrt sich gegen Taylor Swift. Protestsong gegen Swift. Metal Hammer, 3. Februar 2015, abgerufen am 6. Februar 2015.

- ↑ Bloomberg – Are you a robot? Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022.

- ↑ Constance Grady: The Taylor Swift/Scooter Braun controversy, explained. 1. Juli 2019, abgerufen am 3. Februar 2024 (englisch).

- ↑ Béatrice Mathieu: Taylor Swift et ses droits d'auteur : les dessous d'un coup de maître historique. In: L'Express. 10. November 2023, abgerufen am 10. November 2023 (französisch).

- ↑ HYBE becomes global with Ithaca pop stars and BTS under its arm – Pulse by Maeil Business News Korea. Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022 (koreanisch).

- ↑ Benjamin Kanthak: Wie Neonazis Taylor Swift zu ihrer Ikone machen. In: Bayerischer Rundfunk, Puls, Filter. 30. August 2017, archiviert vom (nicht mehr online verfügbar) am 12. März 2018.

- ↑ Hannah Parry: Taylor Swift hailed as 'Aryan goddess' by white supremacist groups in their bizarre claims she is a secret 'Nazi'. In: Daily Mail. 26. Mai 2016, abgerufen am 26. November 2017.

- ↑ Travis M. Andrews: ‘Alt-right’ white supremacists have chosen Taylor Swift as their ‘Aryan goddess’ icon, through no fault of her own. In: Washington Post. 25. Mai 2016, abgerufen am 26. November 2017.

- ↑ Brian Hiatt, Brian Hiatt: Taylor Swift: The Rolling Stone Interview. In: Rolling Stone. 18. September 2019, abgerufen am 23. Dezember 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift on Going Pop. In: Time. 19. Oktober 2012, abgerufen am 10. Oktober 2018.

- ↑ Taylor Swift: 'I was literally about to break'. Abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift äußert sich erstmals politisch. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 8. Oktober 2018, abgerufen am 9. Oktober 2018.

- ↑ Taylor Swift calls out Trump over late-night Minnesota tweet: ‘You have the nerve to feign moral superiority before threatening violence?’ Abgerufen am 21. Oktober 2022.

- ↑ Every Woman Counts: Funny Taylor Swift Interview Before 2008 ACM Awards. Abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ champagne problems lyrics – genius.com. Abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ All Too Well Lyric Keychain. Abgerufen am 31. März 2022 (englisch).

- ↑ Taylor Swift: ‘I was literally about to break’. Abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Makes Generous Donation. GLAAD, 1. Juni 2019, abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift Donates Tennessee Equality. Abgerufen am 29. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift About Black Lives Matter. Abgerufen am 30. März 2022.

- ↑ Taylor Swift endorses Joe Biden for President. 7. Oktober 2020, abgerufen am 13. Februar 2024 (englisch).

- ↑ Annett Meiritz: Der Swift-Faktor – warum Biden die Pop-Ikone braucht und Trump vor ihr zittert. In: Handelsblatt. 2. Februar 2024, abgerufen am 3. Februar 2024 (englisch).

- ↑ Bee-Shyuan Chang: Taylor Swift Gets Some Mud on Her Boots. In: New York Times. 15. März 2013, abgerufen am 7. Februar 2014.

- ↑ Jon Caramanica: Sounds of Swagger and Sob Stories. In: New York Times. 19. Dezember 2008, abgerufen am 7. Februar 2014.

- ↑ Darunter: Gracie AbramsCondé Nast: Gracie Abrams Is Already on to Her Next Moment of Strength. 12. November 2021, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., Kelsea BalleriniCondé Nast: Gracie Abrams Is Already on to Her Next Moment of Strength. 12. November 2021, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., Ruth B.Popping Up: Ruth B. 25. November 2015, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022., Priscilla BlockAngela Stefano: Interview: Priscilla Block Loves Hard, Breaks Harder on Debut EP. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (englisch)., Phoebe BridgersNolan Feeney, Nolan Feeney: Phoebe Bridgers ‘Got Teary’ Recording Her Part on Taylor Swift’s ‘Red (Taylor’s Version)’. In: Billboard. 10. November 2021, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., Camila CabelloGlenn Rowley, Glenn Rowley: Camila Cabello Calls Taylor Swift Her ‘Biggest Inspiration’ After Epic AMAs Performance. In: Billboard. 26. November 2019, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., Sabrina Carpenterhttps://twitter.com/sabrinaannlynn/status/543944334135918594. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022., Sofia CarsonBraudie Blais-Billie, Braudie Blais-Billie: Disney’s Rising Fashion Icon Sofia Carson Talks ‘Back to Beautiful’ & Hosting the Radio Disney Music Awards. In: Billboard. 28. April 2017, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., The ChainsmokersThe Chainsmokers On Rising Hit “Roses,” Debut EP ‘Bouquet’ & Leaving “#Selfie” Behind: Idolator Interview. 23. November 2015, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022., Billie EilishBillie Eilish Hilariously Reacts to Britney Spears Playing Her Music Entertainment Tonight. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., 5 Seconds of SummerPop rock outfit 5 Seconds of Summer have shed their boy band image and are ready to wow fans with a new album. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (englisch)., FletcherThis Artist Went Viral With A Song About Liking A Photo Of Her Ex's New Girlfriend. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (englisch)., Selena GomezSelena Gomez Inspired By Taylor Swift On Her New “Grown-Up” Album 'Stars Dance'. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (englisch)., Ellie GouldingTaylor Swift is an inspiration to me: Ellie Goulding – Indian Express. 17. April 2016, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022., Conan GrayThis Artist Went Viral With A Song About Liking A Photo Of Her Ex's New Girlfriend. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (englisch)., Girl in RedWolfgang Ruth: 7 Influences on girl in red’s Debut, From (Yes) Taylor Swift to Low Serotonin. 30. April 2021, abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch)., GriffLiam Hess: Griff Is Pop’s Next Powerhouse—And She Makes Her Own Clothes, Too. Abgerufen am 31. Oktober 2022 (amerikanisches Englisch).